One of the most important cases to come out of 2023 in Canada examined a rarely litigated provision of Canada's Trademarks Act (the "Act"): section 22. In Energizer Brands, LLC v. Gillette Company, 2023 FC 804 ("Energizer Brands"), Canada's Federal Court (the "Court") clarified the scope and limits of comparative advertising for businesses wishing to make use of a competitor's registered trademark in the advertisement of its products. An issue the Court was tasked with resolving was whether the Defendant's use of the Plaintiff's registered trademarks in its advertising had the effect of depreciating the value of the goodwill attaching to those trademarks in contravention of section 22(1) of the Act.

Section 22(1) of the Act states:

"No person shall use a trademark registered by another person in a manner that is likely to have the effect of depreciating the value of the goodwill attaching thereto."

Background

The Plaintiff, Energizer, and the Defendant, Duracell, are the leading battery brands in Canada and are each other's biggest competitors. In the Canadian household consumer battery market, Duracell has the largest market share of any supplier. Energizer has the next largest share.

Energizer has several Canadian-registered trademarks including the marks "Energizer", "ENERGIZER BUNNY & Design" (shown below) and "RABBIT & Design", all of which are classified by the Canadian Intellectual Property Office in the category of goods associated with the use of batteries.

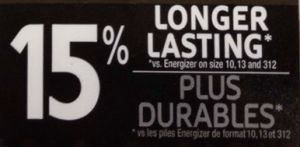

Energizer alleged that from August 2014 to August 2017, Duracell contravened s. 22(1) of the Act by making certain representations in the advertising of its products that had the effect of depreciating the value of goodwill attaching to several of Energizer's registered trademarks. Specifically, Energizer pointed to stickers affixed to certain Duracell batteries sold in Canada featuring claims comparing the performance of those batteries to Energizer's. Below are representative samples of three such stickers affixed by Duracell to its battery products:

(a) "15% LONGER LASTING vs. Energizer on size 10, 13, 312."

(b) "Up To 20% LONGER LASTING vs. the bunny brand on sizes 10, 13 & 312."

(c) "Up To 15% LONGER LASTING vs. the next leading competitive brand."

Analysis

The Court found Duracell to have contravened s. 22(1) of the Act but only with respect to the use of its stickers featuring the "Energizer" trademark name and not to those referencing the phrases "the bunny brand" or "the next leading competitive brand." For Duracell to be found in contravention of s. 22(1), Energizer had to satisfy all four parts of the test set out by the Supreme Court of Canada in Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin v Boutiques Cliquot Ltée, 2006 SCC 23 ("Veuve") by proving, on a balance of probabilities, that:

- Duracell used Energizer's registered trademark with goods or services, regardless of whether they are competitive with those of Duracell;

- that Energizer's registered trademark was sufficiently well known to have a significant degree of goodwill attached to it, although there is no requirement that the trademark be well known or famous;

- that Duracell's use of the trademark was likely to have an effect on that goodwill (in other words, there was a linkage); and

- that the likely effect was to depreciate or cause damage to the value of the goodwill.

With respect to the name "Energizer"

In finding that Duracell contravened s. 22(1) of the Act with respect to the use of its stickers featuring the "Energizer" name, the Court held that Energizer satisfied all four parts of the Veuve test, specifically that:

- Duracell had used Energizer's trademark name in the advertisement of its products;

- that Energizer's trademark name attaches to it a substantial degree of goodwill by virtue of the recognition of the Energizer name as one of the world's largest primary battery manufacturers, and

- that Duracell's use of Energizer's trademark name would have a depreciating effect on the goodwill of the mark as a result of the persistent nature by which repeat customers of Duracell would become aware of the comparative performance claims after each purchase.

With respect to the phrase "the bunny brand"

The Court found Duracell's use of the phrase "the bunny brand" not to be a contravention of section 22(1) of the Act because there was insufficient linkage between the phrase "the bunny brand" and Energizer's bunny trademark from the perspective of the average, hurried consumer. The average, hurried consumer would need to have taken several mental steps to connect the words "the bunny brand" to the image of a pink, bespectacled bunny with large feet and wearing a drum with ENERGIZER on it as a spokes-character for, or trademark of, Energizer. In addition, it is unlikely that such a consumer would have paused long enough at the in‑store battery rack to read the sticker and note the reference to "the bunny brand" written in much smaller print than either the trademark DURACELL or the prominent 20% and the words "LONGER LASTING" to sufficiently connect the "bunny brand" phrase with Energizer's name and mark.

With respect to the phrase "the next leading competitive brand"

The Court found Duracell's use of the phrase "the next leading competitive brand" not to be a contravention of section 22(1) of the Act because this phrase was neither an Energizer trademark nor was it sufficiently similar to any of the Energizer trademarks so as to evoke a connection or association between the two in the minds of an average, hurried consumer. First, there was no evidence that such a consumer would notice this phrase on the busy sticker on which these words appear. In addition, the chances of a consumer taking the time to learn that the description "the next leading competitive brand" refers to Energizer, are at best slim. Accordingly, there could be no depreciation of the value of goodwill in Energizer's marks absent any such link, connection or mental association in the consumer's mind.

Concluding remarks

The Court allowed Energizer's action in part, finding that the Defendant's use of the registered trademarks ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX on the battery packages in the form of comparative performance claims on its stickers contravened section 22 of the Act. The Court imposed a restraining order prohibiting the Defendant, either directly or indirectly, from using the Energizer trademarks and certain of its stickers containing references to Energizer on its battery packages. The Court also awarded Energizer damages in the amount of $179,000 but declined to award any punitive damages.

Energizer Brands provides helpful guidance for business and brand owners wishing either to bring an action or to defend themselves against comparative performance claims involving their products and services or those of their competitors, whichever the case may be.

Those businesses wishing to make use of a competitor's trademarks in the advertisement of their products should examine the context in which these products are displayed to the average consumer in a hurry. These contextual variables include, as the Court remarked, the placement, size, and visibility of the competitor's trademark name on the product.

Businesses wishing to bring an action against comparative performance claims made by a competitor can also look to provisions beyond section 22 of the Act. Subsections 7(a) through (d) of the Act and section 52 of the Competition Act allow parties to seek remedies for false and misleading comparative advertising claims made by a competitor. Specifically, subsection 7(a) of the Act prohibits the making of any false or misleading statements tending to discredit the business, goods or services of a competitor. Section 52 of the Competition Act prohibits any person from making a representation to the public that is false or misleading in a material respect for the purpose of promoting the supply or use of a product or for the purpose of promoting any business interest.

Section 22 of the Act has rarely been judicially considered in the more than seven decades since its enactment. As this provision increasingly becomes the subject of litigation over time, we should expect to see further refinements of its scope and limits.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.