Introduction

Biomethane is indistinguishable from natural gas and can be deployed as a drop-in renewable replacement to natural gas without the need for adaptation of network infrastructure or end-user equipment.

The scale of opportunity in biogas and biomethane production is gaining increasing attention from key energy stakeholders. At the end of 2022, Shell announced a €2 billion investment in the much-coveted Nature Energy, and BP further enhanced its aspirations in this field through the $3.3 billion acquisition of Archaea Energy. The potential has been identified and others will surely follow.

Whilst feedstock availability may limit the extent to which biomethane can completely replace natural gas at current consumption rates, it is clear that the scale of the opportunity is largely untapped1.

The scale of opportunity in biogas and biomethane production is gaining increasing attention from key energy stakeholders

In this article we outline the nature of the opportunity, issues to be considered by investors and policy-makers and the longer-term potential for biomethane in the energy transition mix.

The focus of this article is on biomethane produced from the upgrading of biogas generated from organic feedstock and an anaerobic digestion process. We have not considered in any detail the direct combustion of biogas for power or production of biogas from landfill extraction, wastewater treatment or solid biomass, all of which are also likely to have an important role in the deployment of renewable gas in the years to come.

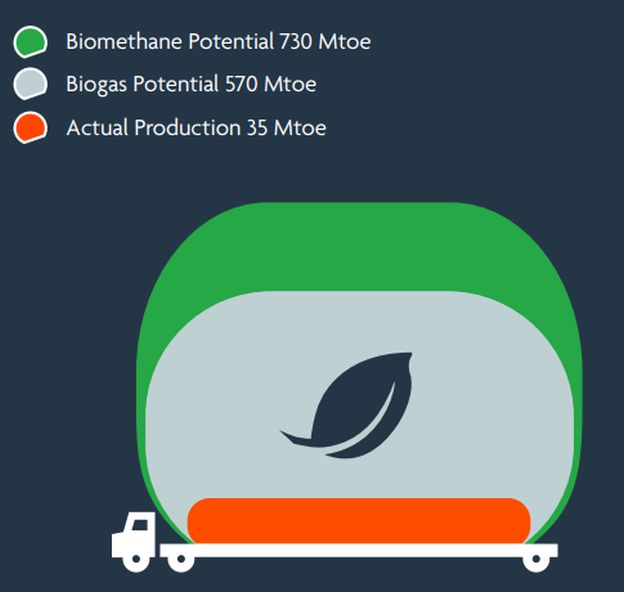

Biogas and Biomethane Production in 2018 Against the Sustainable Potential Today

(Million Tonnes of Oil Equivalent, Mtoe)

Source: Global EV Outlook 2022

Biomethane can therefore offer a near-term solution to energy security issues for countries reliant on natural gas imports. To illustrate this:

The Danish Energy Agency has forecast that through various support regimes, its entire gas grid could be supplied by biomethane in 2034.

The European Union (EU) has set the ambitious biomethane production target of 35 billion cubic meters annually by 2030, following the launch of the Biomethane Industrial Partnership as part of the RePower EU package.

The Case for Biomethane

A Substitute for Natural Gas

Biomethane offers an immediate like-for-like replacement for natural gas without the need for capital investment to upgrade or modify transportation, storage or network infrastructure or end-user equipment and technologies. Put simply, we already have the critical infrastructure and an established use-case.

In 2022, the European Biogas Association estimated that the levelised costs to produce biomethane could be up to 30% lower than the price of natural gas2 , so it offers an immediate cost advantage to counter energy price increases seen recently. The extent to which biomethane will likely remain cheaper than natural gas beyond the short-term is not clear but technological improvements, the scaling of production capacities and government support schemes are likely to continue to create downward pricing pressures.

Biomethane production would seem to be an ideal running mate for clean hydrogen in the decarbonisation of the gas grid and the hard-to-electrify sectors (e.g. steel production, heavy haulage and shipping) and a sensible hedge against the rollout of clean hydrogen, particular as the market and use cases for clean hydrogen are developed.

Sustainable Use of Organic Waste

The feedstock required for anaerobic digestion includes crop residues, animal manure and the organic fraction of municipal waste. If not treated through anaerobic digestion, each will release methane into the atmosphere during the natural decomposition process and will remain a waste disposal problem. In employing anaerobic digestion, the methane is captured, isolated and utilised in a closed environment.

The availability of sustainable feedstocks to produce biogas and/or biomethane is set to grow by 40% over the period to 2040.

The microorganisms used in the anaerobic digestion process convert organically bound nitrogen into a more accessible form for uptake by crops. The by-product of the process— 'digestate'—may therefore be used as a sustainable high quality fertilizer, building organic carbon in agricultural soil, eradicating the waste problem and capturing the very essence of the circular economy. The use of digestate as a green fertilizer also has the benefit of reducing reliance on the import of other fertilizers that rely on energy and carbon intensive production processes.

The use of intermediate crops to produce biogas, such as catch crops or cover crops, is also gaining interest. The use of these crops on fallow land or abandoned land is thought to have a positive impact on soil organic carbon. At the same time, there is a policy to move away from the use of energy crops (i.e. crops that are produced for energy production only) given concerns around land use and the impact on food production. Interestingly, the Danish government has recently relaxed proposed legislative limits on the use of energy crops in the sector in light of the recent energy crisis.

Click here to continue reading . . .

Footnote

1. Together, biogas and biomethane production in 2018 equated to 35 million tonnes of oil equivalent (MOE), whereas the biomethane production potential in the same year was 730 MOE based on sustainable feedstock availability. Furthermore, it is anticipated that the availability of the relevant sustainable feedstock is set to increase by 40% in the period up to 2040. IEA World Energy Outlook Special Report: Outlook for Biogas and Biomethane, prospects for organic growth

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.