In the case of In re Cellect, the Federal Circuit upheld a United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) decision that the patentee's (Cellect's) patents were unpatentable due to Obviousness-type Double Patenting (ODP). In reaching its decision, the Court ruled that Patent Term Adjustments (PTA) and Patent Term Extensions (PTE) should be treated differently when considering ODP.

In particular, the Court held that when different patent family members have different expiration dates based on PTA, the patent family members that expire on an earlier date can be relied upon as the basis for an invalidating ODP challenge as to patent family members that expire on a later date.

The case has significant implications for patent owners with related multi-patent families.

Background

Obviousness-type double patenting

Obviousness-type double patenting (ODP) is a judicially created doctrine in U.S. patent law aimed at preventing the unjustified extension of the patent term. Specifically, this doctrine prevents an applicant or patentee from receiving two patents for claims that are not identical but are still very similar or obvious variations of one another. In essence, it is a way to prevent a single invention—or obvious extensions of a single invention—from being patented more than once, thereby unjustly extending the period of exclusivity, or leaving third parties open to collateral attacks based on the same invention.

Under U.S. patent law, once a patent expires, the invention becomes part of the public domain, free for anyone to use. The doctrine of ODP seeks to balance the interests of the patentee with those of the public by ensuring that the patentee does not get an unfair extension of the monopoly rights granted by a patent.

Terminal Disclaimer

During patent prosecution, and at rare times in litigation, ODP is often overcome by filing a Terminal Disclaimer. A Terminal Disclaimer is a statement disclaiming a portion of the term of a patent. When a Terminal Disclaimer is filed, the applicant essentially agrees that the term of the second patent (the "disclaimed" patent) will end no later than the term of a related, earlier patent. In some cases, The Terminal Disclaimer also specifies that the second patent will be enforceable only during the period when it and the first patent are commonly owned. Thus, a Terminal Disclaimer serves to prevent separate lawsuits from patent family members assigned to different entities for a single or obvious extension of an invention.

Patent Term Adjustment

Under United States patent law, Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) is a mechanism designed to adjust patent terms for time lost due to delays attributable to the USPTO during patent prosecution. Essentially, PTA extends the life of a patent beyond the standard term, typically 20 years from the filing date of the earliest U.S. application to which priority is claimed, excluding provisional applications.

Patent Term Extension

In United States patent law, Patent Term Extension (PTE) is a different concept from PTA, although both relate to extending the life of a patent. PTE is specifically aimed at compensating for the time taken to obtain regulatory approval for products such as pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Given that getting FDA approval can be a time-consuming and expensive process, often taking several years, PTE allows for the extension of a patent's term to make up for some of this regulatory lost time, thereby encouraging investment in high-risk sectors.

In re Cellect

Cellect, LLC appealed a Patent Trials and Appeals Board (Board) decision that found several claims within four of its patents unpatentable for ODP during ex parte reexamination. These reexaminations were initiated by Samsung Electronics Co., a party Cellect had sued for patent infringement.

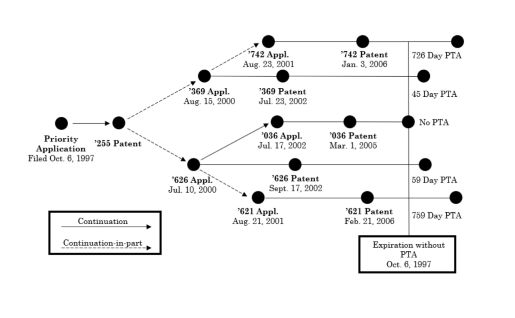

All invalidated claims traced their priorities back to the same parent patent that had already expired. The complex "family tree" for the patents at issue in the case is depicted below.

Cellect based its appeal on three grounds: (1) whether a patent is unpatentable for ODP is determined based on the date of expiration of a patent that includes any duly granted PTA; (2) whether the Board erred in failing to consider the equitable concerns underlying the finding of ODP in the ex parte reexamination proceedings; and (3) whether the Board erred in finding a substantial new question of patentability in the underlyingex partereexaminations.

With regard to the first ground, Cellect relied upon Novartis AG v. Ezra Ventures LLC, 909 F.3d 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2018) and argued that the extension of patent terms due to USPTO delays (PTA) should protect the patents from ODP challenges. According to that case, "ODP does not invalidate a validly obtained Patent Term Extension ("PTE") under 35 USC § 156." Novartis, 909 F.3d 1367, 1372. Cellect argued that ODP should not interfere with a rightfully acquired PTA grant. In other words, Cellect asserted that PTE and PTA extensions should be treated the same for ODP analysis purposes.

However, the Patent Trial and Appeals Board upheld the USPTO's original conclusion, leading to an appeal to the Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit concluded that Patent Term Extensions and PTA should be treated differently in ODP considerations, referencing prior case law and legislative intent. For example, the Court looked to Merck & Co. v. Hi-Tech Pharmacal Co. 482 F.3d 1317 (Fed. Cir. 2007) as an example of how PTE operates differently from the PTA with respect to ODP. Essentially, the Court focused on the different aspects of the statutory framework, noting in the Merck case, that "PTE is not foreclosed by a terminal disclaimer."

In addition, the Court found Cellect's arguments unpersuasive and noted that Cellect had multiple opportunities to submit a terminal disclaimer to mitigate the ODP issues but failed to do so. Specifically, the Court observed that "in the absence of such disclaimers, it would frustrate the clear intent of Congress for applicants to benefit from their failure, or an examiner's failure, to comply with established practice concerning ODP, which contemplates terminal disclaimers as a solution to avoid invalidation of patents claiming obvious inventions." In re Cellect, LLC, Nos. 2022-1293, 2022-1294, 2022-1295, 2022-1296, 2023 U.S. App. LEXIS 22584, *1,*26 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 28, 2023).

Therefore, the Court held "[W]e thus conclude that ODP for a patent that has received PTA, regardless whether or not a terminal disclaimer is required or has been filed, must be based on the expiration date of the patent after PTA has been added. We therefore further conclude that the Board did not err in finding the asserted claims unpatentable under ODP." Id. at *26.

For Patent Owners

For patent owners and applicants, the decision of the Federal Circuit in Cellect will certainly require strategically reviewing patents in extended patent families.

Under the USPTO's "principles of compact prosecution, each claim should be reviewed for compliance with every statutory requirement for patentability in the initial review of the application." (MPEP §2103). However, in Cellect, the Court held these USPTO's principles were insufficient to foreclose a post-grant challenger from alleging that a Patent Examiner failed to consider ODP. In fact, the Court expressly stated, "[t]he Examiner's willingness to issue ODP rejections of claims in other Cellect-owned patent applications but not in the challenged patents and his knowledge of the reference patents do not affirmatively indicate that he considered ODP here." Id. at *32. Therefore, even if the Patent Owner was able to obtain a patent in a continuation and was prosecuted before the same Examiner as the parent, Cellect holds that these facts are insufficient to foreclose a subsequent post-grant challenge under ODP.

One solution offered by the Court to mitigate the post-grant challenge under ODP, is for the Patent Owner "to file terminal disclaimers during prosecution, even in the absence of an ODP rejection." (Id. at *34). However, for most Patent Owners, filing a preemptive terminal disclaimer has not been a common strategy, as there was no real reason to do so prior to Cellect. Other possible solutions include expressly listing the family application in the Information Disclosure Statement (IDS) during prosecution or attempting to reissue the patent after it has been granted. However, recent Federal Circuit case law suggests that both these options may have limited effectiveness and introduce additional risks.

For Patent Challengers

Cellect provides another point of attack for a challenger to invalidate a U.S. patent. In many cases, the greatest value of a patent is realized in its later years of "life," and therefore PTA becomes critical in both a damages and licensing context. However, Cellect now provides an opportunity to invalidate a late-in-life patent that does not require that often expensive and laborious process of finding invalidating prior art. Instead, all that is required under Cellect is for the patent challenger to demonstrate that the patent is an obvious variant of a related patent family member that has already expired.

Summary

Prior to asserting a patent, it is critical to determine whether related patents that may expire at different times could be open to an invalidity challenge under the Cellect analysis. Such an analysis should now be part of an overall strategy review leading up to patent assertion and litigation.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.