The embedding saga continues. The right to embed another's photo or video that was posted on social media has been one of the most hotly litigated issues in copyright law over the past two-plus years. There is now a clear divide between the Second and Ninth Circuits over whether embedding a photo or video is an infringing public display under the Server Rule. (Hint: Second Circuit says yes, Ninth says no.) There is also a question of whether embedding is fair use. (Hint: it depends.) And there is a question of whether posting a photo or video on social media, such as Twitter or Instagram, grants a license to others to embed using the sites' embedding API tool.

Courts recently examining this issue generally concluded that, while posting the content grants a license to Instagram (with the right to sublicense), it is not clear whether Instagram exercises that right in its policy governing its API tool that allows other users to embed that content. My colleague Brian Murphy discussed this extensively and summarized in a graphic that I'm reproducing below (fair use, anyone?):

Instagram itself allegedly weighed in on this issue last summer in an email from Facebook (er, Meta?), which owns Instagram, to Ars Technica, stating:

"While our terms allow us to grant a sub-license, we do not grant one for our embeds API," a Facebook company spokesperson told Ars in a Thursday email. "Our platform policies require third parties to have the necessary rights from applicable rights holders. This includes ensuring they have a license to share this content, if a license is required by law."

Just last week, however, Instagram rolled out a new option enabling users to choose whether to allow embedding of their posted photos or videos. In other words, users can now disable the embed API for the materials they post to their account.

Problem solved? Hardly. What if a user doesn't disable embedding -- does that mean that the user can no longer claim that embedding that content is copyright infringement? It seems like there are three possible arguments:

Argument (1): By allowing users to disable embedding, Instagram is exercising it sublicense right to API users unless the content poster opts out.

This was essentially the original conclusion from Judge Kimba Wood in Sinclair v. Davis before Instagram allowed users to disable embedding. At the time, Judge Wood stitched together the Instagram's Terms of Use, Privacy Policy, and Platform Policy, to conclude that "because Plaintiff uploaded the Photograph to Instagram and designated it as 'public,' she agreed to allow Mashable, as Instagram's sublicensee, to embed the Photograph in its website." Judge Wood pulled back this decision on reconsideration, however, aligning herself with Judge Failla in McGuckin v. Newsweek that while Instagram has a sublicensable license, it was not clear that Instagram had exercised that right.

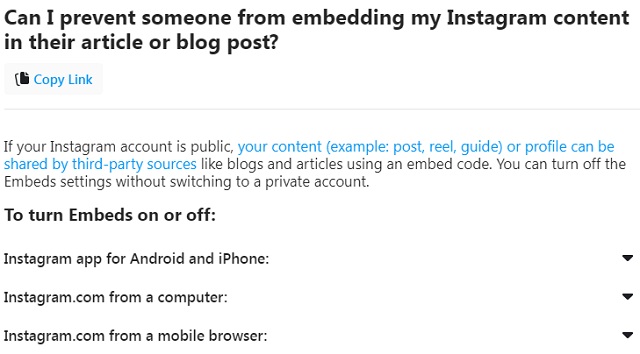

Now that Instagram affirmatively allows users to prevent embedding, does that change the analysis? Look at the new language on Instagram's help page:

Instagram expressly informs users that their content "can be shared by third-party sources." And when you click on the link in the help page, Instagram further clarifies: "Note that for a post or profile to be embedded, your account must be public and the Embeds setting must be turned on." So Instagram is now phrasing the ability of third parties to embed as essentially an affirmative right granted by the content holder. Which brings me to the next argument...

Argument (2): Content holders grant third parties an implied license when they don't disable the embed feature.

I find this argument intriguing. It reminds me of Field v. Google, a 2006 District of Nevada case, which held that the plaintiff granted Google an implied license to display cached links of his web page because he didn't exercise his ability to prevent Google from doing so by using a "no-archive" meta-tag. This case may have been an outlier, but does its logic nevertheless apply here? As noted above, Instagram is essentially portraying the embed option as one that is affirmatively allowed by the user. Assuming this characterization is correct, is the user therefore granting an implied copyright license to embed? And does it matter that a user apparently can only enable (or disable) embedding for one's entire profile, rather than on an image-by-image basis? All good questions, if I do say so myself.

And then there's the third argument:

Argument (3): Nothing has changed.

This one requires little unpacking. The upshot is that users can now disable the embed feature, but that has no impact on whether or not Instagram grants API users a sublicense or whether users grant them an implied license. Perhaps it's a more pragmatic way of looking at the situation: if you want to avoid a circumstance where you have a sue a third party for embedding your content, just prevent them from doing it in the first place. And if you want to know how to prevent them, click here.

This is certainly not the last we've heard on this issue. Just the latest.

This alert provides general coverage of its subject area. We provide it with the understanding that Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz is not engaged herein in rendering legal advice, and shall not be liable for any damages resulting from any error, inaccuracy, or omission. Our attorneys practice law only in jurisdictions in which they are properly authorized to do so. We do not seek to represent clients in other jurisdictions.