This guide covers all related information that a securities practitioner needs when working with an insurance company. It provides an overview of the industry and covers applicable securities laws and regulations, securities offering process, disclosure and corporate governance obligations, stock exchange requirements, commercial and regulatory trends, and practical tips for counsel.

Overview of the Insurance Industry

The insurance industry provides financial protection against a range of risks or perils in exchange for a premium payment. By selecting risks through the underwriting process and pooling such risks from different sources, the insurance company business model aims to collect more in premiums than is ultimately needed to pay out in loss claims. But even if loss claims exceed premiums collected in any year, an insurance company can still be profitable by generating investment income on the premiums collected until they are paid out in loss claims. So, the profitability of an insurance company rests on both its ability to underwrite risk and to manage investment assets.

The industry generally consists of companies providing protection against property and casualty risks, life and annuity risks, and health risks. The industry is further divided among primary insurance companies, who issue contracts of insurance directly to insureds (whether individuals or business entities), and reinsurance companies, who enter into reinsurance contracts with primary insurers to assume risks written by the primary insurer. Reinsurers effectively provide insurance to primary insurance companies.

Insurance and reinsurance are regulated businesses, subject primarily to the laws of the jurisdiction of the company's domicile. Their activities are also regulated, through licensing and other requirements, by the laws of the jurisdictions where they conduct business. In the United States, insurance is primarily regulated at the state, not the federal, level. Since the financial crisis and the adoption of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (111 P.L. 203, 124 Stat. 1376) (Dodd-Frank Act), certain federal oversight has been imposed for the larger systemically important companies. In Europe, among European Union (EU) countries, insurance is regulated primarily by the EU Commission as well as by home country financial regulators.

Insurance companies may take a number of different legal forms. The most common form is a stock corporation, which is typically set up as a wholly owned subsidiary of a non-insurance corporate holding company. These holding companies are the entities most frequently engaged in capital-raising activities on behalf of their subsidiary operating insurance companies. The other common form of insurance entity is a mutual company. Many of the largest companies in the United States (including life insurance companies such as Northwestern Mutual, New York Life, and Mass Mutual and property-casualty companies such as Nationwide and State Farm) are mutual companies whose equity owners are the policyholders. A mutual company would not be able to issue equity securities directly as a means to raise capital. To raise surplus capital for statutory accounting purposes, a mutual company may issue a surplus note, which is a long-term, deeply subordinated debt instrument. The defining characteristic of a surplus note is that no payment of principal or interest may be made without the prior approval of the domicile insurance regulator.

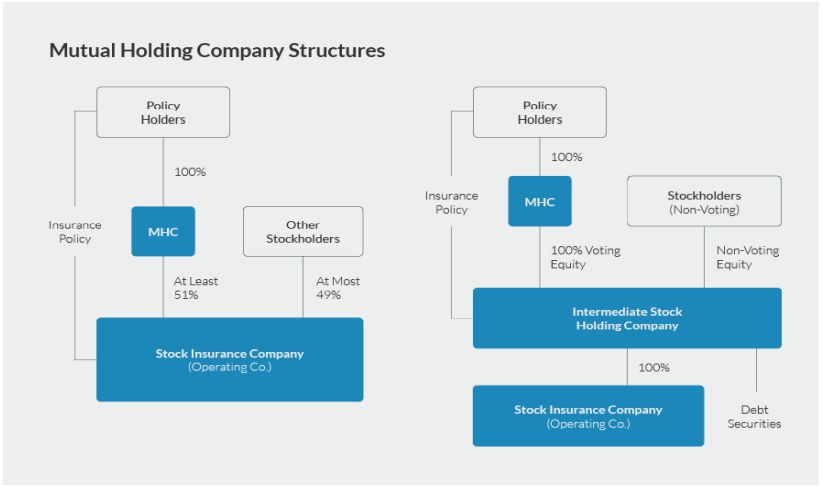

Other corporate forms exist in the insurance industry. Mutual holding companies (MHCs) are holding companies (not operating companies) of stock insurance companies, and the owners of such mutual holding companies are the policy holders of the stock insurance companies. MHCs are generally required to own at least 51% of the stock insurance company. This format allows the downstream stock insurance subsidiary of the MHC to raise voting equity capital. In a typical structure (such as shown in the following diagram on the right), an intermediate stock holding company on top of the operating insurance company (i.e., the parent of the operating company and subsidiary of the MHC) will issue debt securities and non-voting equity securities to raise capital. Many prominent U.S. insurance companies have chosen this form, including Pacific Life, Liberty Mutual, Ohio National, Western & Southern, CUNA Mutual, and Securian Financial.

Another organizational form unique to the insurance industry is known as a reciprocal exchange. In a reciprocal exchange, each policyholder is an owner and risk taker. Policyholders share in the profits and they also are subject to assessments for losses. Reciprocal exchanges are managed by a designated attorney-in-fact which is typically a non-insurance company acting as a managing agent. Prominent reciprocal exchanges in the United States include Farmers and USAA. Other examples include PURE, the New York writer of auto policies, and Erie Indemnity, whose attorney-in-fact is a publicly traded company. For surplus capital, reciprocals rely upon retained earnings and policyholder assessments. They have the ability to borrow and, like mutual insurance companies, they also can issue surplus notes.

Applicable Securities Laws and Regulations

The same federal and state statutes and regulations that govern securities offerings by issuers in other industries apply to insurance companies. These may be summarized as follows:

Securities Act

The principal federal statute regulating securities offerings is the Securities Act of 1933, as amended (73 P.L. 22, 48 Stat. 74, 73 Cong. Ch. 38) (Securities Act). See U.S. Securities Laws. The Securities Act requires each offer and sale of securities in the United States to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) unless an exemption from registration is available. The primary objectives of the Securities Act are to protect investors and prevent fraud in connection with the offer and sale of securities. To accomplish these goals, the Securities Act requires (unless an exemption is available) that investors be provided with a prospectus prior to purchasing any securities being offered. The prospectus, which is part of the registration statement filed with the SEC, will contain extensive information about the issuer and the securities being offered so that investors are able to make a fully informed decision as to whether or not to invest in the securities. Regulation SK promulgated under the Securities Act contains extensive and detailed rules as to what information must be included in the prospectus, but the Securities Act's overriding principal regarding disclosure is that:

- The prospectus should contain all information that a reasonable

person would consider material in making an investment

decision.

- The prospectus must not contain an untrue statement or omission of a material fact.

In reviewing the registration statement, the SEC's focus is solely on the quality and accuracy of the disclosure and not upon the merits of the securities being offered. Secondly, in furtherance of its goals, Section 11 (15 U.S.C. § 77k) of the Securities Act imposes statutory liability against the issuer, its directors, the officers who sign the registration statement, and the underwriters involved in the securities offering if the registration statement contains an untrue statement of a material fact or omits to state a material fact necessary to make the statements included therein not misleading. In the case of the issuer, Section 11 liability is strict. In addition, Section 12(a)(2) (15 U.S.C. § 77l) of the Securities Act provides that any person who offers or sells a security by means of any oral or written communication that contains a similar material misstatement or omission is liable to the purchaser for damages. For further information, seeLiability under the Federal Securities Laws for Securities Offerings.

Not all offerings of securities must be registered with the SEC. Section 4 (15 U.S.C. § 77d) of the Securities Act sets forth a list of transactions that are exempt from its registration requirements, including "transactions by an issuer not involving any public offering." This is referred to as the private placement exemption (Section 4(a)(2)). There is a substantial body of case law, SEC Staff interpretations, and securities law practice dealing with the private placement exemption. The availability of the exemption depends upon an analysis of the particular facts of the offering, including, but not limited to, the:

- Number and sophistication of the investors

- Relationship between the issuer and the investors

- Solicitation efforts of the issuer

In order to provide issuers with certainty regarding a Section 4(a)(2) exemption, the SEC adopted Regulation D which provides a safe harbor exemption for two types of securities offerings, provided certain conditions are satisfied:

- Rule 504 (17 C.F.R. § 230.504) exempting securities

offerings up to $10 million in any 12 month period by issuers that

are not subject to the reporting requirements of the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (73 P.L. 291, 48 Stat. 881, 73

Cong. Ch. 404) (Exchange Act)

- Rule 506 (17 C.F.R. § 230.506) (the most widely used exemption) exempting securities offerings of an unlimited dollar amount to an unlimited number of "accredited investors" and up to 35 non-accredited investors

Another common type of unregistered offering used by issuers, including insurance companies (especially in the case of debt securities), is a Section 4(a)(2) private placement by the issuer to a financial intermediary followed by a resale of the securities by the intermediary to qualified institutional buyers (or QIBs) pursuant to Rule 144A (17 C.F.R. § 230.144a) of the Securities Act or in offshore transactions pursuant to Regulation S (17 C.F.R. § § 230.901- 905), or both methods combined. For further information on private offerings, see Private Placement Process, Top 10 Practice Tips: Private Placements, Equity Offerings Comparison Charts, Regulation D Offerings, and Rule 144A Transactions, and Regulation S Transactions.

To view the full article, please click here.

Originally published by Lexis Practical Guidance.

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global legal services provider comprising legal practices that are separate entities (the "Mayer Brown Practices"). The Mayer Brown Practices are: Mayer Brown LLP and Mayer Brown Europe - Brussels LLP, both limited liability partnerships established in Illinois USA; Mayer Brown International LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated in England and Wales (authorized and regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority and registered in England and Wales number OC 303359); Mayer Brown, a SELAS established in France; Mayer Brown JSM, a Hong Kong partnership and its associated entities in Asia; and Tauil & Chequer Advogados, a Brazilian law partnership with which Mayer Brown is associated. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of the Mayer Brown Practices in their respective jurisdictions.

© Copyright 2020. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.