This is part of a series of articles discussing recent orders of interest issued in patent cases by the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

InVirtek Vision International ULC v. Assembly Guidance Systems, Inc. d/b/a Aligned Vision, No. 20-cv-10857, Judge Burroughs construed two disputed terms in a patent relating to a method of aligning a laser projector for projecting a laser image onto a work surface.

1. "Work surface"

Relying on an embodiment disclosed in the specification, the defendant contended that the scope of "work surface" should be limited to "a surface of a workpiece on which a laser image is projected." The Court rejected the defendant's proposed construction and agreed with the plaintiff that the term's scope should include "any surface on which work is performed."

The Court first found that the patent "expressly disclaims limiting the invention to the embodiment described in the specification," explaining that the disclosures about the broad intended use of the invention beyond the "workpiece" example counsel against limiting the term to the surface of a workpiece. The Court also found that the defendant's proposed construction departed from the term's ordinary and customary meaning, which, without evidence of lexicography or disavowal, would be improper.

Accordingly, the Court construed the term as "a surface on which work is performed.

2. "Identifying a general location of the targets in the work surface"

This disputed term appears in a dependent claim, which recites: "wherein the step of identifying a pattern of the targets is further defined byidentifying a general location of the targets in the work surface." The parties agreed, in the context of the independent claim, that "identifying a pattern of the targets" should be construed as "determining the location and relative positions of the [] targets."

The defendant argued that its proposed construction—"determining the general location, and thus the relative positions, of those targets"—comported with the parties' understanding of the "identifying step" and that there did not "appear to be any difference between" the independent and dependent claims. The plaintiff contended that the defendant's proposed construction would render the dependent claim superfluous and that no construction was needed.

The Court first distinguished the defendant's proposed construction from those found improper by the Federal Circuit, where the construction of an independent claim would exclude an embodiment envisioned by a dependent claim, rendering the dependent claim "not only superfluous but also without any scope." Here, recognizing that "a construction that renders certain claims superfluous need not be rejected," the Court found that the dependent claim "while possibly superfluous, is not meaningless."

The Court nonetheless agreed with the plaintiff that no construction was necessary because the disputed term "does not include any technical terms that are difficult to understand or are otherwise ambiguous."

InTerrie Banhazl d/b/a Heirloom Ceramics v. The American Ceramic Society, No. 16-cv-10791, Judge Burroughs allowed in part and denied in part the plaintiff's motion for pre-judgement interest, ongoing royalties, and additional discovery.

As to pre-judgement interest, the Court rejected the defendant's contention that such relief was improper because "Defendant has . . . not offered any evidence to show that it relied on Plaintiff's conduct [of allegedly delaying suit] and was prejudiced by it."

However, the Court "decline[d] to award prejudgment interest at the Massachusetts

statutory rate of 12 percent and instead applies the prime rate, compounded annually," describing that rate as "excessive." Instead, the Court found that the prime rate was an appropriate compromise and calculated pre-judgement interest at $61,761.16. the Court further granted post-judgement interest at the rate of 2.1 percent.

The Court also allowed the motion as unopposed for ongoing royalties as previously set forth.

Last, the Court denied the request for additional discovery as improperly brought under Rule 59(e).

InMilliman, Inc. v. Gradient A.I. Corp., No. 21-10865-NMG, Judge Gorton construed disputed terms in a patent relating to the anonymization and transmittal of federally protected healthcare data.

1. "Token"

The parties agreed that the plain and ordinary meaning of "token" governs but disputed whether further construction was required. The plaintiffs asked for further construction, contending it was necessary because the term "token" has more than one ordinary meaning. Based on the intrinsic evidence, they proposed the term be construed as: "An identifier associated with an individual that does not reveal the identity of the individual."

The defendants, on the other hand, argued that ordinary meaning was sufficient. In their view, the plaintiffs' proposed construction added additional limitations, unsupported by the intrinsic evidence.

The Court adopted the plaintiffs' proposed construction because the term "token" has multiple ordinary meanings, and the construction would help the jury understand.

2. "Server"

Similarly, the parties disputed whether further construction of the term "server" was necessary. The plaintiffs proposed the construction: "A computer, with a processor and a memory, on a network that provides information in response to requests from another computer." While conceding that the ordinary meaning of "server" may be clear to one of ordinary skill, the plaintiffs sought to provide a construction so that the lay juror would understand.

Agreeing it "would help lay jurors understand a potentially technical term," the Court adopted the plaintiffs' proposed construction.

3. "Encryption server"

The defendants argued no construction of the term "encryption server" was needed.

Plaintiffs conceded that one of ordinary skill would understand that an "encryption server" is a server that performs some sort of encryption. Nonetheless, the plaintiffs contended that their proposed construction—"A 'server' that produces 'tokens' in response to a request"—was necessary to clarify that hashing could be an encryption technique within the scope of the patent.

The Court found that the plaintiffs' proposed construction "d[id] not attempt to define or describe 'encryption'" and would likely confuse the jury. Because "encryption" is a commonly used word and "server" had been construed, the Court concluded that no construction of "encryption server" was needed.

4. "Similarly encrypted"

The Court deferred deciding whether the term "similarly encrypted" is indefinite, as the defendants alleged. In the meantime, the plaintiffs asked the Court to adopt the construction: "Generated such that tokens generated from corresponding information can be compared to one another to detect a match." According to the defendants, this construction was not only unsupported, but would render dependent claims meaningless.

The Court agreed with the defendants, finding the proposed construction ambiguous and likely to confuse the jury. The Court determined that the term "similarly encrypted" has its ordinary meaning.

5. "Medical information that characterizes a group"

For the term "medical information that characterizes a group," the defendants proposed the construction: "Information characterizing health status of the group as a whole." According to the defendants, this special meaning of the term was supported by amendments to the specification in which "medical information" was replaced with "information" and references to "health status" were added.

The plaintiffs disagreed, arguing no construction of the term was necessary because it could be easily understood both by one of ordinary skill and lay jury. Further, they criticized the defendants' proposed construction for introducing limitations.

The Court found that the intrinsic evidence did not support the defendants' proposed construction. Because the term could be readily understood, the Court construed the term to have its ordinary meaning.

6. "Absent authorization"

With respect to a set of five "absent authorization" terms, the plaintiffs contended no construction was required because the terms used only words readily understood by a jury.

The defendants proposed a construction adding two limitations: "to produce the (healthcare/medical) information" and "in response to the request." As support for one of those limitations, defendants pointed to language in the patent specification.

The Court noted that a limitation from the specification should not be read into the claims. Further, because the five "absent authorization" terms included "all non-technical words without special meanings," the Court concluded that no construction was necessary.

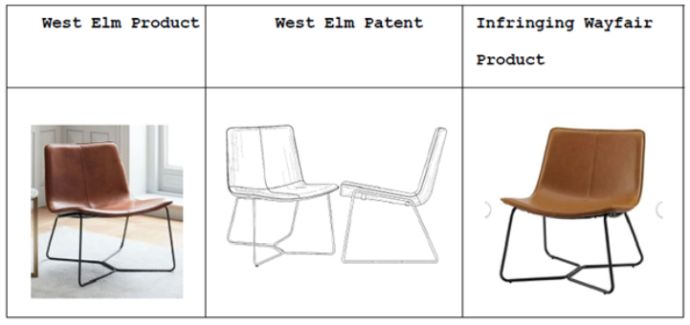

InWilliams-Sonoma, Inc. v. Wayfair Inc., No. 1:21-12063, Judge Saris allowed in part and denied in part the defendant's motion to dismiss. The plaintiff ("WSI") has multiple design patents associated with its "West Elm" brand, and its complaint contends that the defendant "Foundstone collection" includes products that infringe "are so highly similar to West Elm's patented products that an ordinary observer would be confused by the imitation." The Court offered one example from the Complaint:

The plaintiff also asserted counts for false advertising in violation of Section 43 of the Lanham Act and violations under the Massachusetts (Chapter 93A) and California unfair competition laws. The defendant moved to dismiss these claims.

Lanham Act False Advertising Claim

The plaintiff alleges that three statements by Wayfair constitute false advertising. Those statements, in full, read:

- "Foundstone" followed by the text "Only at Wayfair."

- Wayfair's "exclusive brands team has been hard at work on Foundstone a Wayfair-exclusive collection of attainable and updated mid-century furniture and décor."

- Wayfair's "hand-curated collections are filled with the best in popular pieces, timeless designs, and looks you'll find only at Wayfair—all at prices that fit your budget."

The plaintiff argued that "Wayfair's factual statements regarding the origin of its designs or that its products are 'only at Wayfair,' 'exclusive' to Wayfair or 'looks you'll only find at Wayfair' constitute false or misleading representations." The defendant argued "that these phrases cannot be read in isolation, as WSI focuses on theproducts, when the phrases read in the entirety of the advertisement, Wayfair contends, focus on thecollections" and thus are literally true. (Emphasis by the Court.) The Court found that "Wayfair is correct that 'context is crucial.'"

More specifically, the Court observed that inDastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23 (2003), the Supreme Court found that the phrase "'origin of goods' in the Lanham Act referred to the producer of the [goods], and not the producer of the (potentially) copyrightable or patentable designs that the [goods] embodied." As such, the Court found that it ultimately need not address the alleged falsity of the above statements because they "do not relate to the properties, capabilities, or characteristics of the goods" but rather "more closely relate to misrepresentations about the origin of goods and [thus] are not cognizable . . . ."

Massachusetts Chapter 93A

The Court held that while "a plausible Lanham Act claim also states a Chapter 93A claim," a Chapter 93A claim can survive where a Lanham Act claim is precluded. Observing that the plaintiff "points to several unfair acts and practices, such as holding those designs out as Wayfair's own and freeriding of WSI's goodwill and advertising," the court denied the motion to dismiss as to the Chapter 93A claim.

California State Law Claims

The Court observed that while Federal courts remain divided in its application, the majority view is set out "[i]nKwikset Corp. v. Superior Ct., 246 P.3d 877, 888 (Cal. 2011), [where] the California Supreme Court held that consumer plaintiffs 'must demonstrate actual reliance on the allegedly deceptive or misleading statements, in accordance with well-settled principles regarding the element of reliance in ordinary fraud actions.'" Applying this majority view, the Court dismissed the California state law claims, finding that the complaint did not satisfy the reliance requirement.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.