Holding:

In Pavo Solutions LLC v. Kingston Technology Co., No. 21-1834 (Fed. Cir. June 3, 2022), the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ("Federal Circuit") affirmed a jury verdict in the Central District of California awarding $7.5 million in compensatory damages, enhanced by 50 percent, for willful infringement.

Background:

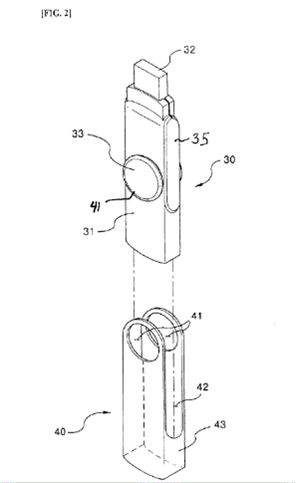

The patent at issue (U.S. Patent No. 6,926,544 ("the '544 patent")) describes a USB flash memory apparatus with a cover that protects the USB port from damage and foreign substances, as shown in Fig. 2.

The '544 patent purported to solve prior-art issues associated with detachable USB covers because they were often lost or loosened, causing damage to the USB port. The '544 patent describes a cover that is "not completely separated from a main body so that loss of the cover is prevented." '544 patent Abstract. The "flash memory main body" contains a case with a "hinge protuberance." Id. at col. 3 ll. 11-14. The open sides in the cover would allow the flash memory main body to be covered but not separated, thus solving the issues of loss or damage. Independent claim 1 of the '544 patent, however, recited "the hinge protuberance on the case for pivoting the case with respect to the flash memory main body[.]" Id. at Claim 1 (emphasis added).

Pavo Solutions sued Kingston for infringement of the '544 patent. Pavo Solutions argued that the infringement was willful because Kingston continued with its USB device sales despite notice of infringement in 2012. Kingston then challenged the '544 patent at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board ("Board"). The Board upheld many of the challenged claims and found several others were unpatentable for obviousness.

During claim construction, the district court found that the phrase "pivoting the case with respect to the flash memory main body," had a clerical error and corrected the claim language by replacing the word "case" with the word "cover." Pavo Sols., LLC v. Kingston Tech. Co., Case No. SACV 14-1352, 2018 WL 5099486, at *4 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 10, 2018) ("Claim Construction Order"). The district court determined that the error was "evident from the face of the patent" because the case was part of the main body and therefore would not be able to pivot. Id. Furthermore, "[t]he correction was not subject to reasonable debate . . . because Kingston's proposed alternative construction—replacing 'flash memory main body' with 'cover' so that the claim reads 'pivoting the case with respect to the cover'—resulted in the same claim scope." Id. at *3. Additionally, the district court noted that the prosecution history was consistent with the correction, unlike Kingston's expert testimony which was inconsistent with the intrinsic record. Id. at *4.

The jury found that Kingston infringed three claims of the '544 patent that the PTAB upheld, awarding $7.5 million in damages, half of the damages that Pavo Solutions originally sought. The district court later added $3.8 million in damages to the jury award, along with $2.3 million in interest.

Federal Circuit Decision:

Among the issues on appeal, the court's correction of a claim is addressed and discussed in this post. That is, the Federal Circuit reviewed the standard for district court correction of a claim:

A district court may correct "obvious minor typographical and clerical errors in patents." Novo Indus., L.P. v. Micro Molds Corp., 350 F.3d 1348, 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2003). Correction is appropriate "only if (1) the correction is not subject to reasonable debate based on consideration of the claim language and the specification and (2) the prosecution history does not suggest a different interpretation of the claims." Id. at 1354. The error must be "evident from the face of the patent," Grp. One, Ltd. v. Hallmark Cards, Inc., 407 F.3d 1297, 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2005), and the determination "must be made from the point of view of one skilled in the art," Ultimax Cement Mfg. Corp. v. CTS Cement Mfg. Corp., 587 F.3d 1339, 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2009). In deciding whether a particular correction is appropriate, the court "must consider how a potential correction would impact the scope of a claim and if the inventor is entitled to the resulting claim scope based on the written description of the patent." CBT Flint Partners, LLC v. Return Path, Inc., 654 F.3d 1353, 1359 (Fed. Cir. 2011).

Pavo Solutions, at *7-8.

The Federal Circuit upheld the district court's correction of "case" to "cover" in the claims. First, the error was an obvious minor typographical or clerical error because it was clear from the full context of the claim language and the specification. Under these circumstances, the district court properly corrected the claim language, even if the correction altered the claimed structure. Second, the Federal Circuit agreed that the correction was not subject to reasonable debate because both the district court's correction and Kinston's proposed correction would result in the same claim scope. Additionally, the Federal Circuit held that the prosecution history does not suggest a different interpretation of the claims because the applicant, the examiner, and the Board consistently characterized the claims as describing "pivoting the case [] within the cover" ... "allowing the cover to pivot," ...and "a cover . . . having a hinge element functioning with the case," despite the errors in the claims. Id. At *14.

The Federal Circuit distinguished Chef America, Inc. v. Lamb-Weston, Inc. from the present case. 358 F.3d 1371, (Fed. Cir. 2004). In Chef America, the Federal Circuit refused to construe the phrase "heating the resulting batter-coated dough to a temperature in the range of about 400º F. to 850 º F," to refer to the oven temperature, rather than the dough temperature, because the original claim language clearly and unmistakably referred to the dough temperature. Id. at 1374. Unlike in Chef America, the Federal Circuit concluded that the errors in the claims of Pavo Solutions were obvious in light of the entire claim language and the specification. The claim in Pavo Solutions also did not make sense facially while the claim in Chef America described a realistic but undesirable result. In addition, unlike Pavo Solutions, the patent owners in Chef America made no attempt to correct the error.

As to the district court's finding of willful infringement, the Federal Circuit affirmed and held that Kingston could not hide behind the obvious minor clerical error to escape the jury verdict of willful infringement.

Take-aways:

- Mistakes and errors can occur in the prosecution of a patent application and the printing of a patent. These errors, which appear in the granted patent, range from minor errors, like simple spelling errors, that arise in the printing process, to errors that result in claims that cover a different scope than what the inventors had a right to claim.

- In terms of correction by a district court, if the error is obvious from the "face of the patent" and it can only be corrected in one way (i.e., no ambiguity in how the claim should read), then a district court is allowed to correct the error via claim construction. As noted by the Federal Circuit in Hoffer v. Microsoft Corp., 405 F.3d 1326, 1331 (Fed. Cir. 2005):

This error in dependency of claim 22 is apparent on the face of the printed patent, and the correct antecedent claim is apparent from the prosecution history. . . . Absent evidence of culpability or intent to deceive by delaying formal correction, a patent should not be invalidated based on an obvious administrative error. . . . When a harmless error in a patent is not subject to reasonable debate, it can be corrected by the court, as for other legal documents.

- Correction procedures are not available to cure some fatal defects in the granted patent. For example, procedures are not available to cure §112 shortcomings, such as the failure of the specification to supply an enabling disclosure, an adequate description of the invention, or the best mode contemplated by the inventor with respect to the invention claimed in the patent. The AIA removed the need to correct the best mode with its amendment to 35 U.S.C. §282 removing failure to disclose the best mode as grounds for invalidity or unenforceability for proceedings commenced on or after September 16, 2011, although the statute does not define what is the meaning of "proceedings."

- If correcting an error, such as a typographical error, would amount to redrafting the claim, the court will refuse to make such a correction and the error can be fatal. For example, in Novo Industries, L.P. v. Micro Molds Corp., 350 F.3d 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2003), the Federal Circuit held that the district court erred in correcting "formed on a rotatable with said support fingers" to read "formed on and rotatable with said support finger" because, while it was clear that the claim contained an error, it was not indisputably clear that the error should be corrected by changing "a" to "and." Id. at 1357-58. Without knowing what correction was necessarily appropriate, or how the claim should have been interpreted, the Federal Circuit held the claim invalid for indefiniteness.

- Judicial correction is available for obvious minor typographical and clerical errors in patents, only if (1) the correction is not subject to reasonable debate based on consideration of the claim language and the specification, and (2) the prosecution history does not suggest a different interpretation of the claims.

- If these conditions are met, even corrections that alter the structure of the claimed invention may be appropriate. See Lemelson v. General Mills, Inc., 968 F.2d 1202, 1203 (Fed. Cir. 1992); ITS Rubber Co. v. Essex Rubber Co., 272 U.S. 429, 441-43 (1926). The change in the structure of the claimed invention does not necessarily indicate a change in claim scope. The courts also are not limited to correcting errors that result in linguistic incorrectness. Pavo Solutions, at *10.

- The stricter approach in Chef America, however, remains a warning for claim drafters. There is a line of case law where the court refused to correct a claim, finding that the patent drafter should bear the responsibility for any error in drafting. See, e.g., Halliburton Energy Services, Inc. v. M-I LLC, 514 F.3d 1244 (Fed. Cir. 2008) ("We note that the patent drafter is in the best position to resolve the ambiguity in the patent claims[.]"); Sage Products, Inc. v. Devon Industries, Inc., 126 F.3d 1420 (Fed. Cir. 1997) ("Given a choice of imposing the higher costs of careful prosecution on patentees, or imposing the costs of foreclosed business activity on the public at large, this court believes the costs are properly imposed on the group best positioned to determine whether or not a particular invention warrants investment at a higher level, that is, the patentees."); Athletic Alternatives, Inc. v. Prince Manufacturing, Inc., 73 F.3d 1573, 1581 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (when there is an equal choice between a broad and narrow meaning of a claim, the public notice function is better served by interpreting the claim more narrowly).

- An accused infringer cannot escape willful infringement merely because an asserted claim contained an obvious error. When drafting an opinion of counsel for a claim containing an error, be sure to address infringement issues based on the corrected claim language.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.