There are a number of different types of protection that can be used to protect a novel plant cultivar – Plant Patents, USDA Plant Variety Protection (PVP), Utility Patents directed toward a particular variety, foreign Plant Breeder Rights (PBR), Trademarks, etc. – and this is a generally an area of IP law that is poorly understood by most IP attorneys, other than those who specialize in the field. However, it is helpful for every IP attorney to have at least a basic knowledge of the various plant IP options, what the differences are between them, and when each one is applicable so that you can at least let your clients know that several options exist and that there are numerous factors that need to be considered when formulating an IP strategy.

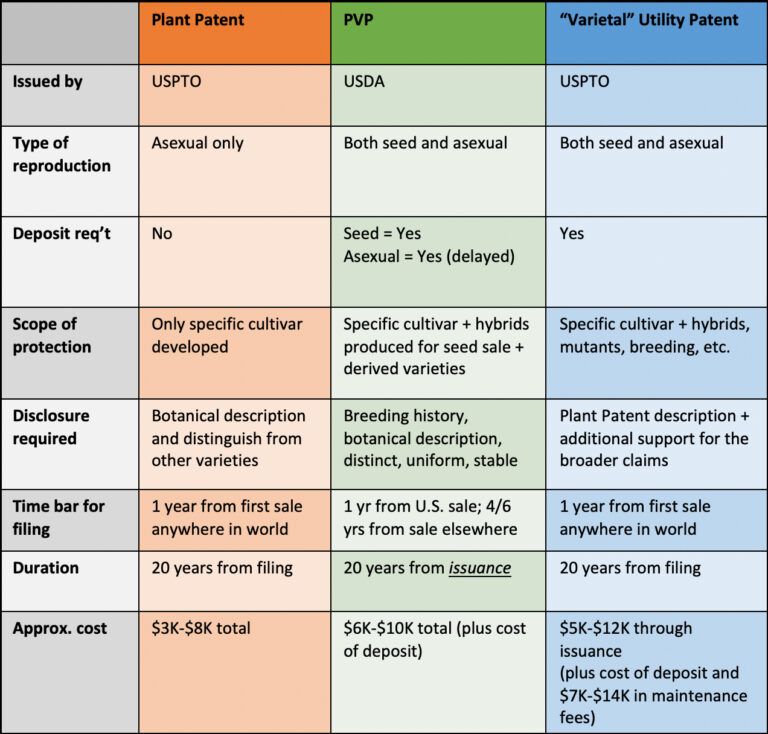

Focusing on the various options in the U.S. for protecting a new plant cultivar, Plant Patents are only applicable to asexually reproduced plant cultivars. Like other types of patents, these are issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The protection lasts 20 years from date of filing, and the scope of protection covers making using, selling, or importing the particular plant cultivar that was developed. These are often viewed as a basic protection that provides a "first line of defense" type protection for a novel plant cultivar. Though there are a number of similarities to Utility Patents, there are also key differences in how they are prosecuted. For example, Plant Patents have only a single claim that is directed toward the particular asexually reproduced plant cultivar that was developed. Further, the new matter rules applicable to Plant Patents are quite different than those for Utility Patents. Additionally, Plant Patents have lower filing and issue fess, and there are no maintenance fees that need to be paid following issuance.

Utility Patents that are directed to a specific plant cultivar can also be obtained. These are prosecuted much like any other Utility Patent and fall under the same standard rules and regulations. Several distinctions exist between a Plant Patent and a Utility Patent directed toward a novel cultivar. A Utility Patent can be obtained for a plant cultivar that is produced either asexually or sexually, and a Utility Patent generally requires the deposit of plant material (seed or tissue culture), while a Plant Patent does not. Most importantly, Utility Patents allow for the inclusion of multiple claims, which allows the patentee to seek somewhat broader and more diverse claim scope than can be obtained using a Plant Patent.

PVP certificates are a different animal altogether. They are issued by the USDA as opposed to the USPTO, making the rules, regulations, and processes for filing and prosecuting these application quite different. They can be used to protect both sexually and asexually reproduced varieties, and both the cost and scope of protection is generally intermediate to that of Plant Patents and Utility Patents. Moreover, the filing deadlines, bar dates, and term differ from those of the two patent options. This makes PVP protection an ideal choice (over the patent options) in certain situations.

A summary of the three types of protections is presented in the chart below, and all of this obviously provides only the most basic information on these three different types of protection available in the U.S. for new plant cultivars. It is also important to note that these options are not mutually exclusive, and in some cases there may be reasons that justify obtaining more than one type of protection for a novel plant cultivar. With all of that said, depending on a number of factors, including the type of plant, how it was initially produced, how it will be reproduced and ultimately used commercially, where and when it was first sold, what type of specific competitive activities you are concerned about, and what type of budget pressures exist, some of these options may be more applicable than others. Thus, it is important to ensure you are receiving advice from someone very knowledgeable in the area of plant IP when developing an IP strategy for a new plant cultivar.

Originally Published 3 February, 2021

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.