All imports and exports are regulated by US Customs and Border Protection (CBP or US Customs; formerly the US Customs Service), which is the largest federal law enforcement agency of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). The history of CBP and the fines, penalties, and forfeitures (FP&F) process goes back to July 4, 1789. The second Act of the First Congress of the United States was to establish a system of tariffs on imported goods to fund the new federal government. Shortly thereafter, Congress established the U.S. Customs Service and subjected merchandise to fines, penalties, and forfeitures for breaches of the law.

The authority to initiate seizures and impose fines was initially vested in Customs field personnel and all fines, penalties, and forfeitures required judicial enforcement. There was no provision allowing the granting of equitable relief. In 1797, the authority to grant equitable relief was vested in the Secretary of Treasury. Over time, as the Secretary's responsibilities increased, the authority to remit or mitigate penalties was delegated to subordinate officials in the Department and the Customs Service.

In 2003, the US Customs Service was transitioned to CBP, the nation's first comprehensive border security agency with a focus on maintaining the integrity of the nation's boundaries and ports of entry. Today, CBP has full authority—pursuant to delegation of authority—to assess penalties and seize merchandise for violations of customs laws. CBP has been delegated broad authority to remit, mitigate, cancel, or compromise claims for forfeitures, penalties, and liquidated damages. See Treasury Decision 00-58.

CBP's enforcement authorities include:

- Seizures. Taking possession of merchandise that is subject to seizure under federal statutes. Detentions typically precede seizures.

- Penalties. Imposing a monetary penalty against an entity for a violation of laws enforced by CBP.

- Liquidated Damages. Issuing a claim for liquidated damages for breach of a bond condition under 19 C.F.R.Part 113.

CBP has been delegated broad authority to assess, remit, mitigate, cancel, or compromise penalties and liquidated damages claims and to seize merchandise for violations of Customs or other laws enforced by the CBP pursuant to 19 U.S.C. § 1618.

Practice Tip: CBP frequently updates Guidance Documents for the public. The most recent Enforcement Process document related to the FP&F process was modified on Feb. 25, 2020, and is titled Customs Administrative Enforcement Process: Fines, Penalties, Forfeitures and Liquidated Damages.

Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Act (CAFRA) & NON-CAFRA

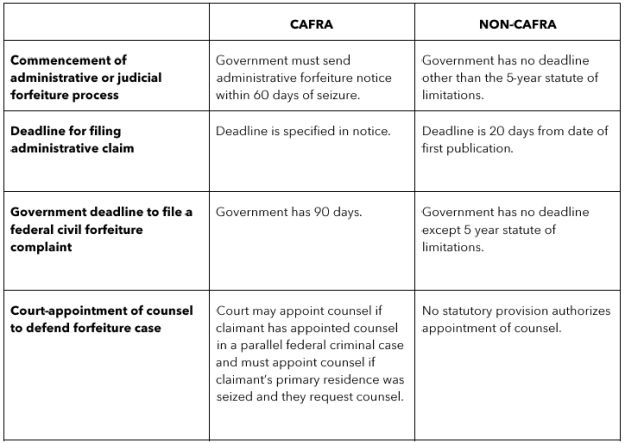

There are two classes of seizure cases: CAFRA cases and non-CAFRA. CAFRA comes from the Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Act of 2000 (CAFRA) which is codified at 18 U.S.C. 983. The Act was passed in an effort to reform civil asset forfeiture laws and to make the procedure more equitable. Seizures by US Customs are typically NON-CAFRA.

There are important procedural differences between a CAFRA seizure and a Customs seizure. For example:

Practice Tip: Most CAFRA provisions and requirements are not applicable to forfeitures under the Tariff Act or traditional customs forfeitures such as failure to declare, conveyances facilitating unlawful importations, or exports contrary to law. Hence, the bulk of seizures and forfeitures handled by Customs will be governed by NON-CAFRA rules and regulations.

CBP Detention & Seizures

Detention Process

Customs laws and regulations provide US Customs officers at all 328 ports of entry the ability to stop and search persons or merchandise and make admissibility decisions. Before goods are seized by CBP, they typically go through the detention process.

When a US Customs officer (CBPO) believes merchandise should be detained the CBPO has five days to decide whether to release or detain the goods. Should the CBPO decide to detain the goods, the CBPO is required to send to the importer or passenger a Notice of Detention, pursuant to 19 C.F.R. 151.16(c), no later than 5 business days after their decision to detain the goods, stating the:

- Date the merchandise was detained.

- Reason for the detention.

- Anticipated length of the detention.

- Nature of the tests or inquiries to be conducted.

- Nature of any information which, if supplied to US Customs, may accelerate the disposition of the detention.

Practice Tip: It is common for importers not to receive detention notices timely—or at all—and for the notices not to contain the five requirements above that are essential for importers to advocate for the release of their detained goods.

Practice Tip: During the detention period, it is also common to have a customs broker or counsel communicate with CBP to discuss the rationale for detention and what information is required to obtain a CBP release.

Practice Tip: CBP regulations (19 C.F.R. 151.16(e)) state that CBPO's should make a final determination within 30 days from the date the merchandise is presented to CBP for examination, or the goods are deemed excluded. It is common for this period to be extended by CBP and an importer can request an extension.

CBP must have probable cause to believe that there was a violation of a customs law or other law enforced by CBP to initiate a seizure case. Examples of violations and merchandise that may be seized:

- Restricted Merchandise. Merchandise allegedly violates restrictions imposed by law or other partner government agencies laws—e.g., US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Transportation (DOT), US Department of Agriculture (USDA), and Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) to name a few.

- Prohibited Merchandise. Controlled substances, counterfeit goods, pornography.

- Undeclared, Unreported, or Smuggled Merchandise. Goods undeclared by persons upon entry into the US—e.g., unreported currency over $10,000.

- Goods Which Aid or Facilitate the Illegal Importation of Merchandise. Items that are unmanifested or used to conceal illegal goods.

Seizure Process

When merchandise is seized, the merchandise will be appraised, and the CBPO will transfer the case to the Fines, Penalties, and Forfeitures (FP&F) office and a FP&F case number and paralegal will be assigned.

Practice Tip: Request the FP&F case number from the CBPO prior to contacting FP&F to find out the paralegal assigned. The first four digits of a FP&F case number is always the fiscal year, the second four digits are always the port code.

The paralegal assigned will issue a seizure notice to all parties that have a known interest in the goods. FP&F's authority is provided for in Parts 171 and 172 of the Customs Regulations—and any party with a financial interest in the goods has a right to fight for the release of the seized property.

An Election of Proceedings form accompanies the "Seizure Notice" providing the following options:

- Administrative Petition. Occurs before forfeiture proceedings are initiated.

- Offer in Compromise. Pursuant to 19 U.S.C. 1617.

- Abandonment. Abandoning all title and legal right to the property and requesting CBP to immediately begin administrative forfeiture proceedings.

- Referral for Court Action. Filing a claim and cost bond for CBP to refer the case to the US Attorney's Office.

- Request for Administrative Proceedings. Request CBP start forfeiture proceedings, while still preserving the right to file a petition, an offer in compromise or the filing of a claim and cost bond before the proceedings conclude.

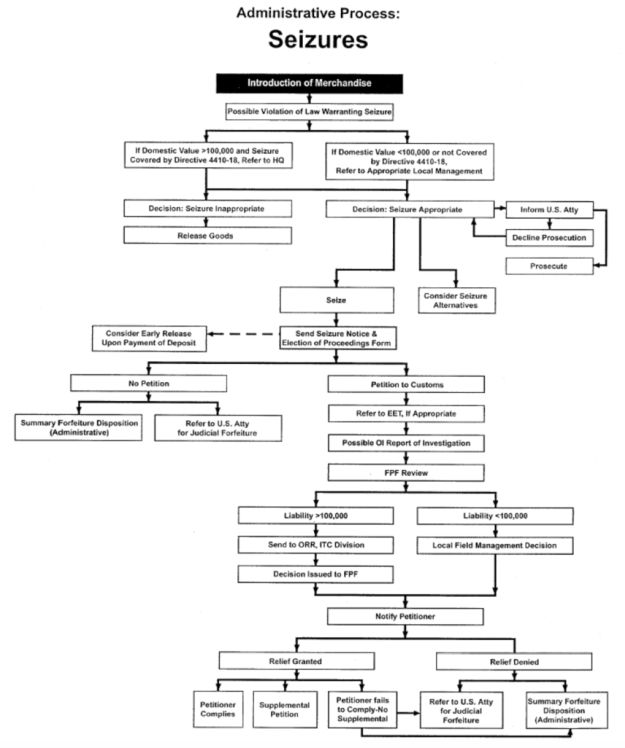

CBP has outlined the administrative process for seizures in the chart below, which is taken from page 24 of the Customs Administrative Enforcement Process: Fines, Penalties, Forfeitures and Liquidated Damages.

Practice Tips:

- Extensions may be requested before the expiration of the 30 day period to respond and are routinely granted when requested timely.

- If you have received a Notice of Seizure, do not delay contacting a Customs attorney who can help you navigate the process. For example, it is a typical recommendation to first file a petition for relief as results are routinely based upon FP&F's mitigation guidelines.

- CBP recently rolled out an online portal that allows companies to file an "ePetition." The portal allows petitioners to submit and check the status of Petitions to FP&F.

- Should a petition be denied, there is still an option to file a supplemental petition, offer in compromise, or file a claim and cost bond to refer the matter for court action.

- FP&F cannot accept a filing without a completed Election of Proceedings form selecting the option you choose. FP&F is now accepting electronic submissions (via email or the portal). It is highly recommended to obtain confirmation of receipt after sending your submission (if submitted online, ensure you keep your reference ID).

- Should you choose to file an administrative petition, it must be filed within 30 days of the date of the seizure notice and contain legal arguments and the valid reasons why CBP should release the seized merchandise.

- When goods are valued over $100,000 the FP&F paralegal is mandated to send the case to CBP Headquarters, Office of Regulations and Rulings. When this occurs, it is common for decisions to take more than one year.

- If needed, you (or your counsel) may file a timely request for an extension to the FP&F paralegal assigned to your case. A 30-day extension is routinely granted. Obtaining an extension will allow your Customs attorney to work with you in obtaining all the documents needed to draft a complete petition with your arguments.

- In certain cases, it is appropriate to request early release of the seized merchandise. For example, when you can prove the underlying seizure was not appropriate, and/or the merchandise at issue is not prohibited.

- If no Petition is filed and no claim and cost bond given, Customs will proceed to forfeit the property by publishing a notice for three weeks online. After three successive weeks of posting, the merchandise is deemed forfeited and typically either destroyed or sold at auction.

A petition should include:

- A description of the property seized.

- The date and place of the violation or seizure.

- The facts and circumstances that justify mitigation or remission.

- Proof that the petitioner has interest in the seized property.

Practice Tip: CBP makes decisions based on the agency's Mitigation Guidelines. Mitigation guidelines are updated and published in CBP's informed compliance publications and also in the Customs Bulletin & Decisions publication. Mitigation guidelines provide terrific guidance on CBP's decision making process and a sense of what CBP's ultimate decision will be. For example, in making a decision, the agency looks at a series of mitigating and aggravating factors.

Practice Tip: It is a best practice for a petition to also include a listing of all applicable mitigating factors such as:

- Prior good record of violator,

- Inexperience in importing.

- Cooperation with CBP's' investigation.

- Inability to pay the fine—demonstrated by documentary evidence including, but not limited to, income taxes for the past three years.

Aggravating factors include:

- Criminal conviction relating to transaction.

- Repetitive violation of the same import restriction.

- Evidence of intentional importation contrary to US law.

Practice Tip: A good petition will always include the specific link between your case, supporting documents and evidence, and the Mitigation Guidelines. When you cite to the Mitigation Guidelines it is essential to explain why your case fits the Guidelines or if it should be looked at differently, citing 19 U.S.C. 1618 as the statute that empowers CBP's deciding official to reach a decision that is deemed reasonable and just. The Mitigation Guidelines are not set in stone and allow for flexibility, discretion and the evaluation of extraordinary circumstances and a case-by-case basis analysis. The deciding official uses the Mitigation Guidelines but could deviate from them if they deem the circumstances for doing so are reasonable and just per 19 U.S.C. 1618.

Once the administrative petition is received and reviewed by the FP&F paralegal, a decision will be made to either grant or deny the petition.

Petition is Granted

If CBP grants the petition, the petitioner must generally submit a notarized Hold Harmless Agreement, pay for storage fees, and pay any applicable assessed penalty. A CBP decision is valid for a limited period of time—typically 30 days.

Petition is Denied

If CBP denies the petition, the petitioner may file a supplemental petition, which is essentially an appeal. Typically, an importer has 60 days to file a supplemental petition with CBP—some ports shorten the timeframe to 30 days, which is provided for in 19 C.F.R. 171.61.

During the supplemental petition review process, the FP&F paralegal:

- Will decide whether to grant further relief pursuant to its delegation of authority. See: Treasury Decision 00-58.

- Can affirm their decision—to deny relief—and then the case is sent to a higher-level decision-maker within CBP to Headquarters (CBP HQ). An attorney from CBP HQ is assigned and reconsiders the case from scratch and makes an independent decision on the case. The FP&F paralegal will include the CBP HQ decision in its final decision sent to Petitioner.

Upon receipt of CBP's decision of the supplemental petitioner, if petitioner is satisfied with the decision, the petitioner must generally submit a notarized Hold Harmless Agreement, pay for storage fees, and pay any applicable assessed penalty. A CBP decision is valid for a limited period of time—typically 30 days. If the petitioner is not satisfied with the CBP decision, the petitioner still has an opportunity to submit an "Offer in Compromise" (OIC) to CBP.

Offer in Compromise

An OIC must include the actual check from petitioner with the written offer, stating the specific amount of your check is offered to the government in an effort to avoid further expenses of defending a challenge to the seizure. The offer in compromise allows for CBP to settle the case for an amount that is deemed acceptable and is deemed to be "in the best interest of the Government."

CBP Monetary Penalties

In addition to seizing goods, CBP also has authority to issue monetary penalties against individuals for violations of customs laws. These penalties may be assessed in addition to or in lieu of a seizure or other penalty like a referral for criminal prosecution.

In the following cases, prior to issuing a penalty notice, CBP is required to first issue a prepenalty notice:

- Commercial fraud and negligence (19 U.S.C. 1592).

- Drawback penalties (19 U.S.C. 1593a).

- Customs broker penalties (19 U.S.C.1641).

- Recordkeeping penalties (19 U.S.C. 1509).

- Falsity or lack of manifest (19 U.S.C.1584(a)(1)).

- Equipment and vessel repairs (19 U.S.C. 1466).

The prepenalty notice shall contain the following information:

- Describe the merchandise, if applicable.

- Set forth the details of the error in the manifest, if applicable.

- Specify all laws and regulations allegedly violated.

- Describe all material facts and circumstances which establish the alleged violation.

- State the estimated loss of duties, if any, and, taking into account all circumstances, the amount of the proposed penalty claim or claim of forfeiture, as appropriate.

Upon receipt of a prepenalty notice, the recipient has the right to make a written and oral presentation to CBP. Generally, the alleged violator has 60 days to file a petition—unless there is a potential statute of limitations concern.

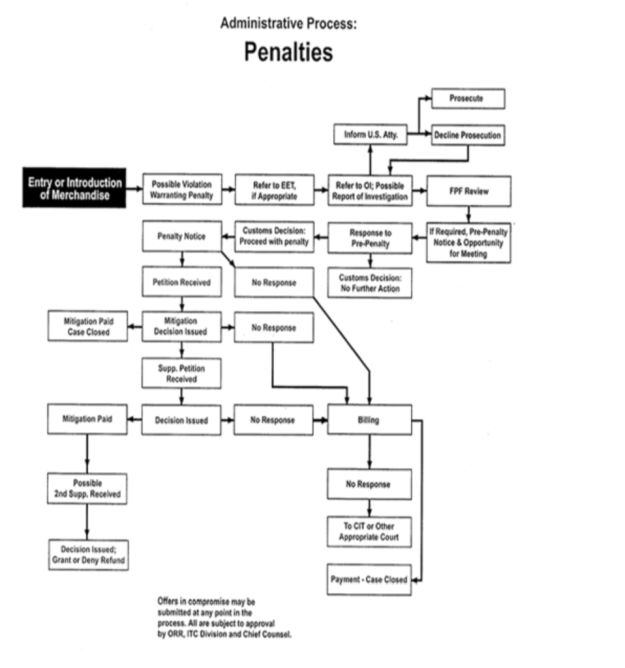

CBP has outlined the administrative process for penalties in the chart below, which is taken from page 39 of the Customs Administrative Enforcement Process: Fines, Penalties, Forfeitures and Liquidated Damages.

Practice Tip: Review the elements of the violation and the date of the violation—or date it was discovered—are clearly established in CBP's penalty notice (CBP Form 5955A). To calculate the statute of limitations (SOL), review the oldest entry involved in the alleged violation and add five years. If the SOL has expired, CBP can no longer issue a penalty for that violation. If the SOL is close to expiring, expect CBP to request a notarized SOL waiver to consider your petition. In many cases, it is beneficial to sign the SOL waiver because it allows the individual or company against whom a penalty was assessed to take advantage of the administrative petition process.

Practice Tip: It is essential to review the underlying violation alleged. For example, in order for CBP to assert negligence—a violation of 19 U.S.C. 1592—there had to have been an absence of reasonable care on the part of the importer. If you have evidence that the importer did utilize reasonable care at the time of importation, then that should be presented to CBP in the prepenalty petition—and oral presentation—with an assertion that that CBP cannot proceed with a penalty case alleging negligence due to the use of reasonable care.

Practice Tip: If a valid prior disclosure was submitted to CBP and the importer still receives a prepenalty notice, the petition should allege a prior disclosure was filed and request the appropriate cancellation or mitigation.

After reviewing the petition, CBP will either proceed to issue a penalty claim or issue a written statement that they have chosen not to assess a penalty.

The following penalties do not require a prepenalty notice:

- Penalties for aiding unlawful importation.

- Drug related manifest penalties.

- Counterfeit trademark penalties.

- Conveyance arrival, reporting, entry, and clearance violations.

In these cases, CBP will move straight to the issuance of a penalty claim.

CBP Liquidated Damages

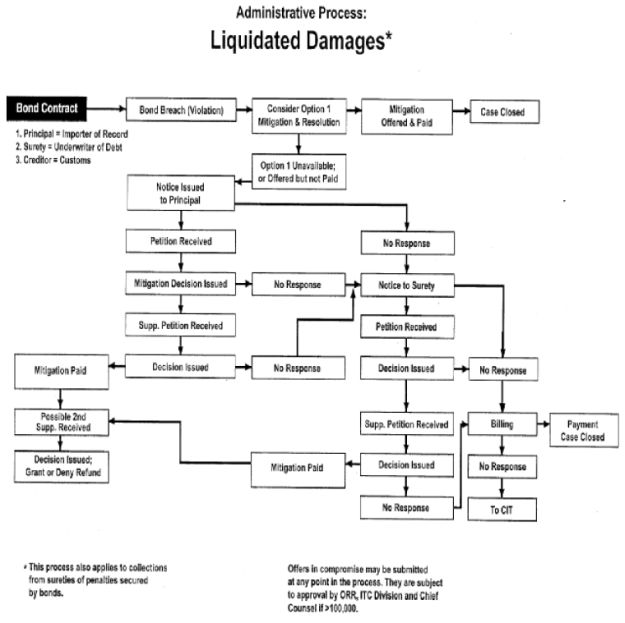

A third type of enforcement tool available to CBP is the issuance of liquidated damages. This type of enforcement is utilized when there is a breach of a condition under a customs bond. For example, CBP requires all importers and customs brokers to have a valid customs bond in place.

If a principal—importer of record—breaches an obligation under its bond, CBP may issue a claim for liquidated damages. Examples of bond breaches occur when entries are filed late or failing to pay or late payments of customs duties. Generally, there is 60 days—from the date on the liquidated damages claim—to file a petition.

The FPFO can make ultimate decisions on petitions received when the amount of the liquidated damages claim does not exceed $200,000, and if the amount is over, the decision will be made by CBP HQ.

When CBP discovers a violation of a bond condition, CBP has discretion to pursue an "Option 1" resolution where the alleged violator pays a much lower pre-set amount to settle the case quickly and eliminate the filing and processing of a petition. If CBP does not provide an Option 1 resolution on the liquidated damages claim, the alleged violator has the option to file a petition requesting mitigation or cancellation of the liquidated damages claim.

CBP has outlined the administrative process for liquidated damages in the chart below, which is taken from page 45 of the Customs Administrative Enforcement Process: Fines, Penalties, Forfeitures and Liquidated Damages.

Practice Tip: CBP has a number of Informed Compliance Publications (ICPs) in the "What Every Member of the Trade Community Should Know About: ..." series. Each publication will have an original publication date, and any subsequent revisions.

Conclusion

FP&F's seizure, penalty, and liquidated damages process can be complicated and time consuming to resolve and CBP is investing heavily in new artificial intelligence technology to proactively target companies. Now, more than ever, having the right experts assisting you throughout the process is essential.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.