Taylor Swift just can't ... give it the slip ... skip out on it ... pay no mind to it ... Oh, Jiminy Cricket. I'm just going to say it. She just can't SHAKE IT OFF.

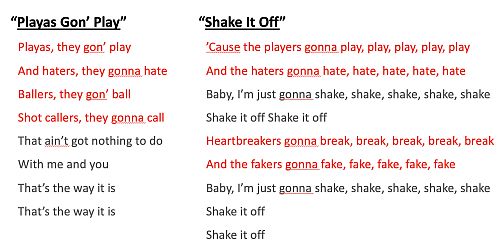

The "it" is a lawsuit that has been going on for years in California. The plaintiffs are Sean Hall and Nathan Butler who co-wrote the song "Playas Gonna Play," which was recorded by the female group 3LW's and released in 2001. (Listen here.) Nearly 15 years later, Swift co-wrote, recorded and released "Shake It Off." (Listen here.) The plaintiffs sued Swift (and her co-authors and their publishers), alleging copyright infringement arising from alleged lyrical and structural similarities between the songs. (The plaintiffs do not contend that the compositions share any significant rhythmic, melodic, harmonic, or other musical similarities.) Here is a side-by-side showing the lyrics at issue:

In 2018, the district court granted the defendants' motion to dismiss on the grounds that the the short phrase in the plaintiffs' composition - "Playas, they gonna play/And haters, they gonna hate" - "lack[ed] the modicum of originality and creativity required for copyright protection." (Opinion here.) In a terse, unpublished decision, the Ninth Circuit reversed, holding that the complaint "plausibly alleged originality." (See the original opinion and revised opinion.) On remand, the defendants tried again to get the case thrown out by arguing, under the merger doctrine, that the unprotectable idea underlying plaintiffs' lyrics - "people will do what they will do" - had merged with those words, rendering them unprotectable too. In a 2020 opinion, the district court rejected this attempt because the plaintiffs' "lyrics, as alleged, are more complex than people will do what they will do, and it is not abundantly clear from the Complaint that there are sufficiently few means of expressing this idea." (Opinion here.)

Hoping that the third time would be the charm, the defendants moved for summary judgment after discovery. Earlier this month, Judge Michael W. Fitzgerald denied the motion.

First, the defendants argued, once again, that the phrases/lyrics at issue are in the public domain and, therefore, are not entitled to protection as musical or literary works. Judge Fitzgerald held that this argument was foreclosed by the Ninth Circuit:

"As indicated at the hearing, this argument is really a motion for reconsideration of the Ninth Circuit's ruling. It's not as if the lyrics in the record now are materially different than what the Complaint alleges. The Ninth Circuit already acknowledged that, at minimum, Plaintiff's characterization of the work at issue (i.e. "a six-word phrase and a four-part lyrical sequence" from "Playa Gon' Play") was enough to sufficiently allege originality. As discussed at the hearing, Defendants have not shown that circumstances have changed since the Ninth Circuit opinion. Originality is sufficiently shown, when viewed in the light most favorable to Plaintiffs, even if the phrases are in the public domain." (Cleaned up.)

Second, the defendants argued, in the alternative, that, even if the phrase in "Playas Gon' Play" was subject to limited copyright protection, it was not substantially similar to the lyrics in "Shake It Up." In response, the plaintiffs pointed to several elements in the selection and arrangement of the four-part lyrical sequence at issue that allegedly also appear in "Shake It Up," including (1) the combination of tautological phrases, (2) parallel lyrics, and (3) grammatical model "Xers gonna X." While noting that the defendants may "have made a strong closing argument for a jury," Judge Fitzgerald held that they had failed to show that there were no genuine issues of triable fact on the question of substantial similarity:

"As Plaintiffs point out, even though there are some noticeable differences between the works, there are also significant similarities in word usage and sequence/structure. In addition to the combination of the phrases 'Playas, they gonna play / And haters, they gonna hate' appearing almost identically in Shake, and other similarities discussed above, Plaintiffs also argue that Playas included a four-part structure that Swift replicated by making reference to select groups with negative connotations, and that these similarities ultimately deliver the same message at the heart of their songs: that "we should not be concerned with what other people say and do, trusting in ourselves instead." Though it is debatable whether this broader message is indeed communicated through the structural similarities alleged, or is an idea that is not entitled to copyright protection, it is clear that there are enough objective similarities amongst the works to imply that the Court cannot presently determine that no reasonable juror could find substantial similarity of lyrical phrasing, word arrangement, or poetic structure between the two works." (Cleaned up.)

In light of the Ninth Circuit's opinion, the result here is one, perhaps, we could have predicted all too well. This means that the bad blood between the litigants will continue, and the delicate task of determining whether, and to what extent, the disputed phrase in "Playa Gon' Play" is entitled to protection under copyright law will fall to the jury.

Hall v. Swift, No. CV 17-6882-MWF (ASx) (C.D. Cal. Dec. 9, 2021)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.