My Apple News feed nourishes me, on a daily basis, with news about politics, the Real Housewives, and beautiful homes that fall into the category of "if you have to ask, you can't afford it lingerie." The home design articles often include floorplans for the subject properties, presumably to give voyeurs like me a better sense of scale and flow. I suspect that the publications rarely, if ever, get permission to show the floorplans from the copyright owners in the architectural works that they depict. Should they?

The short answer is: maybe, at least in the Eighth Circuit.

The plaintiff built homes in Missouri that included a triangular atrium design with stairs (which, I imagine, is quite distinctive). When the owners of two of the homes listed their properties for sale, their brokers, as is customary, created floorplans which it posted online for potential buyers to see. The plaintiff sued for copyright infringement, alleging that the defendants had infringed their copyrights in the architectural works (i.e., the homes) when they created and published the floorplans without authorization. The district court granted summary judgment to the defendants, holding that the scope of copyright protection in an architectural work did not extend to preventing others from creating floorplans of the work. The Eighth Circuit reversed.

The exclusive rights in a copyrighted work, set forth in § 106, are not absolute and are subject to a number of exceptions and limitations. (See 17. U.S.C. §§ 107 - 121.) At issue in this case is § 120(a), which limits the scope of protection for architectural works. That section provides:

"The copyright in an architectural work that has been constructed does not include the right to prevent the making, distributing, or public display of pictures, paintings, photographs or other pictorial representations of the work, if the building in which the work is embodied is located in or ordinarily visible from a public place."

The district court held that the floorplans were "pictorial representations" of the homes, and that, therefore, § 120(a) was a complete defense to the plaintiff's claims. After carefully parsing through the statutory language, the Eighth Circuit reached the opposite conclusion. Here's a brief summary of the court's analysis.

1. Because "pictures" is not defined in the statute, the court looked to the ordinary meaning of the term. The OED defines "picture" as "[a]n individual painting, drawing, or other representation on a surface, of an object or objects." Although floorplans "might possibly fit" within the definition of "pictures" or, alternatively, might qualify as "other pictorial representations," the court felt that the broader statutory context indicated that Congress had not intended floorplans to be covered by § 120(a).

2. Congress "knew how to describe floorplans with more specificity than by simply referring to them as 'pictures'." Indeed, Congress used "alternative, better-fitting language" in other sections of the Copyright Act, specifically in the definition of "pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works" (which includes any "technical drawings, including architectural plans") and in the definition of "works of visual art" (which excludes from coverage "technical drawing"). The court concluded that if Congress had intended § 120(a) to encompass floorplans, it "would've said so more explicitly."

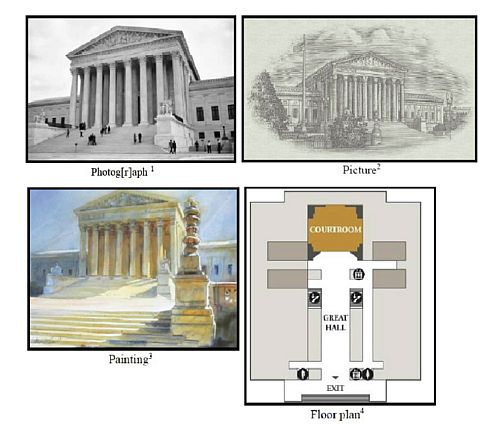

3. The court noted that the series of words in § 120(a) - i.e., "pictures, paintings, photographs or other pictorial representations" - all connote works that capture artistic expression. In the court's view, floorplans are not (at least typically) created for artistic purposes; instead, they serve a "functional" or "practical" purpose, including informing potential buyers of the layouts and interiors of homes for sale. Applying the principle of noscitur a sociis (a word is known by the company it keeps), the court concluded that floorplans "do not share the common quality" that the terms in § 120(a), posses. The court included in its opinion this illustration - submitted by the plaintiff in its brief - to support its conclusion that pictures, paintings and pictorial representations" are qualitatively different from floorplans:

In the court's words, "[o]ne of these images is not like the others."

4. Applying the interpretive principle known as ejusdem generis (when "general words follow specific words in a statutory enumeration, the general words are construed to embrace only objects similar in nature to those objects enumerated by the preceding specific words"), the court concluded that the words that preceded the catch-all "other pictorial representations" "call to mind, once again, categories of expression rather than function." Accordingly, the court was unwilling to read into "pictorial representations" a meaning broad enough to encompass functional floorplans.

5. Finally, the court noted that § 120(a) applies only when "the building in which the work is embodied is located in or ordinarily visible from a public place." Since "floorplans typically stem from someone's access to the interior of a building," this provided additional support for the conclusion that Congress "did not appear to be directing § 120(a) toward floorplans."

While the case will be remanded to the district court for further proceedings, all hope is not lost for the defendants. The court concluded by noting that other potentially viable defenses may exist that excuse the use of the floorplans:

"Nothing we say in this opinion is meant to undermine any defense other than the one found in § 120(a). It may be that many of the hypothetical uses that the defendants posit would be protected by some other defense. The fair-use defense immediately comes to mind. See 17 U.S.C. § 107. In fact, the defendants here raised fair use below, but the district court did not reach its potential application because it concluded that § 120(a) applied. We need not resolve that matter because we leave it to the district court on remand to do so in the first instance. Just because we close one door to protection from liability doesn't mean that others aren't standing open."

Designworks Homes, Inc. v. Columbia House of Brokers Realty, Inc., 2021 WL 3612784, __ F.4th __ (8th Cir. Aug 16, 2021)

This alert provides general coverage of its subject area. We provide it with the understanding that Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz is not engaged herein in rendering legal advice, and shall not be liable for any damages resulting from any error, inaccuracy, or omission. Our attorneys practice law only in jurisdictions in which they are properly authorized to do so. We do not seek to represent clients in other jurisdictions.