This brief article explains why and when a public disclosure invalidates a patent. Most inventors and designers do understand that new developments need to be kept confidential prior to making a decision as to whether to apply for legal patent protection or not.

The confidentiality requirement in many territories around the world is required by law, and the UK is one of these.

To be granted a valid patent, one of the requirements is that your invention must be novel. Disclosing your invention publicly in any form before the filing date of your patent application can prove fatal to your patent application (or granted patent).

However, before taking the leap into patenting an idea, the designer will often want to first test their development. One or more prototypes are therefore often required.

The trap or pitfall which often catches people out is that testing a prototype in a public space can also count as a public disclosure. But, does testing a prototype on private land count as a 'public disclosure'? HH Judge Hacon was brought in to consider this question in a recent case in the British High Court.

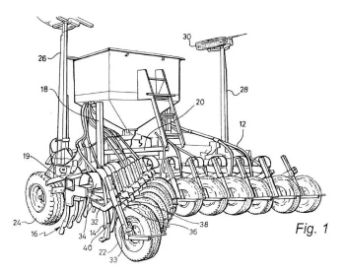

The patentee (patent owner), Claydon Yield-o-meter Limited, owns British patent 2400296, relating to a new type of seed drill (a machine for planting crop seeds). The invention in question is shown in Figure 1 below:

The patentee sought to enforce their patent against a competitor, Mzuri Limited, who retaliated by claiming the patent was invalid.

The judge had to consider whether the patentee had publicly disclosed the invention, when they tested their prototype over two days in a field of their farm. The field was private land, but a public footpath ran alongside the field, separated by a 6-foot-tall hedge.

Unfortunately for the patentee, the hedge had three gaps through which the public could view the private field from the public footpath.

It is irrelevant whether anyone actually did take a stroll along the public footpath on those two days: the mere possibility of a sighting of the invention by a member of the public is enough.

Thus, HH Judge Hacon declared the patent invalid due to public disclosure by the patentee prior to the filing of the patent application.

So, how can you hopefully avoid invalidating your patent if you need to test a prototype? Possible suggestions may include the following:

1. Only trial a prototype once patent pending.

However, this may not always be practical in some cases as the trial-and-error phase may be crucial to developing a functioning invention.

2. If testing a prototype is necessary before filing, do it in a private environment which is not overlooked by or accessible to the public.

Specifically, it would be best to avoid storing or using your prototype in a room which may be visible to a passer-by walking on the street and looking through a window. Admittedly, in the case of a large agricultural machine such as the seed drill in the above case, testing the machine indoors might be difficult. If testing outdoors is the only option, ensure the public has no access to the invention.

Where the public access is restricted, but the invention is still visible to the public and it is obvious how the invention functions when seen (as in the above court case), make sure that the public has no direct line of sight of the invention, even from a distance.

Interestingly, HH Judge Hacon in the above court case commented on the use of technical equipment to gain access to the invention. He considered that a member of the public might reasonably be expected to carry a mobile phone having a camera with a zoom function. The zoom function could enable the member of the public to view details of a prototype not discernible to the naked eye. In such a case, the prototype might be considered disclosed to the public.

On the other hand, a member of the public is not generally considered to commonly carry a drone fitted with a camera. Therefore, whilst blocking up the three gaps in the hedge with a fence might have been enough to prevent the prototype testing from being deemed a public disclosure in the above case, this is increasingly less likely to be the case going forwards due to drones, camera sticks, and other equipment becoming more common.

In any case, obscuring how the invention works may be an option, for example, by cloaking the apparatus or encasing it in a housing, so that it is a 'black box'. There is no disclosure if a member of the public knowledgeable in the field of the invention is unable to work out how the invention works.

3. Keep your invention a secret from anyone not involved in the project.

Restricting who has access to the information is one of the best ways to avoid accidental (or deliberate) disclosure by a third party.

4. If you must involve a third party (including friends and family), ensure they know the matter is confidential.

A disclosure in confidence is not deemed to be a 'public' disclosure. Tell them that your invention is confidential, or better yet, get something in writing if you can, in case of any fallout at a later date.

A non-disclosure agreement (NDA) prior to the disclosure would be best. However, in practice, getting friends and family to sign an NDA may be a difficult topic to broach. An option could be to text or email the friend or family member prior to disclosing the invention to them, telling them that your invention and the disclosure you are about to make are both confidential.

5. In certain countries, such as the US or Japan, inventors benefit from a 12-month grace-period to file a patent application following public disclosure.

Unlike the UK/Europe, this 12 month disclosure grace period can be extremely useful. If you do disclose your invention publicly in Japan or the USA, make sure your patent application is filed in that country no later than 12 months after your disclosure.

The USA and Japan are not the only countries having a disclosure grace period, so you may want to check whether other countries of interest have a similar system.

By following the above tips, you can hedge against your patent being declared invalid!

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.