Due to the combined effects of the devaluation in the Turkish Lira and the regulations which ensure that the drug prices in Turkey are among the lowest in the world; engaging in arbitrage in the pharma industry became more and more attractive for opportunistic companies that are working on innovative ways of collecting drugs from the market and reselling those in export markets. This practice is hazardous for the citizens of Turkey as it may lead to a shortage of vital drugs in the Turkish markets and cause critical health risks for a considerable part of the population. Moreover, the widespread presence of parallel exports may also disincentivize pharma companies from supplying the Turkish market with more (especially the expensive new technology) drugs at current regulated prices. This is because parallel export of low-priced medicines to other countries where prices are dearer would eat into the profits of the pharma companies in those countries. Hence, it is of utmost importance to guarantee that opportunistic parallel traders are prevented.

While it may seem that the foregoing is exclusively related to the health-sector policies of Turkey, in reality, this is largely a competition law issue since the only actors that can realistically prevent such behavior are the pharma companies themselves. Even in the presence of legislation that bans parallel exports of drugs in Turkey, it would be nigh impossible for the law enforcement agencies to track down everyone profiteering from arbitrage. Hence, it is up to the pharma companies to ensure that no one but the people who are in actual need can lay their hands on the vital drugs they supply. One of the most common tools utilized by the pharma companies were direct and indirect export bans imposed on their distributors (i.e., pharmaceutical warehouses – "PWs"), contractually prohibiting them from engaging in parallel exports and from selling the relevant products to any third party that is suspected of similar conduct. Pharma companies also relied on tracking tools and contractual remedies (e.g., right to terminate and contractual penalties) to render those prohibitions more effective.

The Turkish Competition Authority ("TCA") has long recognized the necessity of direct and indirect export bans in Turkey and almost always allowed pharma companies to impose such restrictions on PWs. The latest Roche/CoReNa Decision1 of the TCA clarified that these bans are per se legal under Turkish competition law. Unfortunately, parallel exports came to be so lucrative recently (mainly due to the devaluation of the Turkish Lira) that the efficacy of contractual prohibitions imposed on the PWs diminished. This is evidenced by increasing shortages that are attracting large public attention and reaction. As a matter of fact, the Turkish Pharmacists' Association has just announced that there are difficulties in procuring a total of 645 different drugs.2 The risk was exacerbated as decreased supply (mainly caused by an increase in parallel exports and the low regulated prices) coincided with increased demand (due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

The problem is that there are too many PWs in Turkey, and it is just a matter of time that some of them give in to temptation and reach for the bounty presented in the form of parallel exports. The incentives of giving in are much higher for PWs that are relatively less invested and thus have much less to fear from the repercussions they would have to face "if" they get caught. This situation led pharma companies to come up with new solutions. The most reasonable alternative seemed to be to reduce the size of the distribution network and to only work with the PWs that are completely trusted. This was exactly when the pharma companies hit the wall formerly put up by the TCA.

A Little Bit of History...

A brief dive into the history of Turkish competition case law is needed here to understand why the wall was erected in the first place.

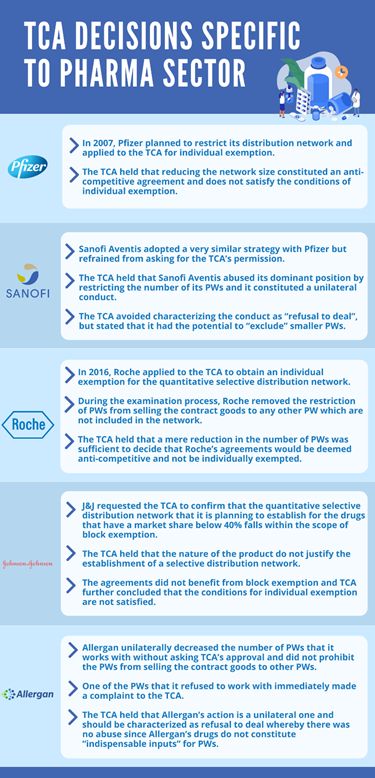

In 2007 Pfizer no longer wanted to work with a total  of 90 PWs of varying sizes and

desired to deal with the ones that actually mattered for it and

planned to restrict its distribution network to PWs that have a

market share above a modest threshold of 2.5%. In practice, this

meant that Pfizer would only work with 7 PWs (the market share of

the other 83 were below the 2.5% threshold). To make sure that this

reduction in the network size (and some contractual restrictions

that are not relevant for our purposes) is compatible with the

Turkish competition law, Pfizer applied to the TCA for an

individual exemption. This led TCA to take a quite controversial

decision, which became an established precedent (only for the

pharma industry). While it seemed that reducing the network size

was unilateral conduct of Pfizer, the TCA held that it constituted

a part of an anti-competitive agreement, which prevented the

agreement from satisfying the conditions of the individual

exemption. Ironically, the reason why the TCA made this tendentious

interpretation was to protect the security of supply. Indeed the

TCA was concerned that Pfizer's action could lead to the

elimination of smaller PWs (especially if similar practices were

also adopted by other pharma companies) and make it harder for some

pharmacies (especially in remote locations) to get access to drugs

and overall the pharmacies would be deprived of the upstream PWs

competition which provides them certain financial benefits TCA

concluded its decision by referring to the number of pharmacies

operational in the country, and the PWs purchasing drugs from the

pharma companies without limitation actually enable the efficient

distribution of the drugs even to rural areas.

of 90 PWs of varying sizes and

desired to deal with the ones that actually mattered for it and

planned to restrict its distribution network to PWs that have a

market share above a modest threshold of 2.5%. In practice, this

meant that Pfizer would only work with 7 PWs (the market share of

the other 83 were below the 2.5% threshold). To make sure that this

reduction in the network size (and some contractual restrictions

that are not relevant for our purposes) is compatible with the

Turkish competition law, Pfizer applied to the TCA for an

individual exemption. This led TCA to take a quite controversial

decision, which became an established precedent (only for the

pharma industry). While it seemed that reducing the network size

was unilateral conduct of Pfizer, the TCA held that it constituted

a part of an anti-competitive agreement, which prevented the

agreement from satisfying the conditions of the individual

exemption. Ironically, the reason why the TCA made this tendentious

interpretation was to protect the security of supply. Indeed the

TCA was concerned that Pfizer's action could lead to the

elimination of smaller PWs (especially if similar practices were

also adopted by other pharma companies) and make it harder for some

pharmacies (especially in remote locations) to get access to drugs

and overall the pharmacies would be deprived of the upstream PWs

competition which provides them certain financial benefits TCA

concluded its decision by referring to the number of pharmacies

operational in the country, and the PWs purchasing drugs from the

pharma companies without limitation actually enable the efficient

distribution of the drugs even to rural areas.

Noticing that the decision of the TCA was not based on strong legal foundations, Sanofi Aventis decided to adopt a very similar strategy with Pfizer but refrained from asking for the TCA's permission. Yet, the TCA did not back down and took another questionable decision, holding that Sanofi Aventis abused its dominant position by restricting the number of PWs it will work with. The TCA realized, this time, that this was unilateral conduct and not an anti-competitive agreement. The decision was thought-provoking because the theory of harm (which was quite ambiguous) was brand new. While the TCA carefully avoided characterizing Sanofi Aventis's conduct as "refusal to deal" (probably because it would be impossible to find an abuse under that characterization), it stated that Sanofi Aventis's conduct had the potential to "exclude" smaller PWs. This was an unprecedented approach because the TCA had never argued that a unilateral conduct that was not aimed towards a competitor could be deemed as exclusionary under existing laws before. Sanofi Aventis remained an exception. However, it was sufficient to deter further attempts on the part of pharma companies to reduce their network size (unilaterally or through an agreement).

While the pharma companies did not knock on the door of the TCA with similar large-scaled attempts to reduce network size, every now and then, they had problems with individual PWs to whom they did not want to supply drugs (mainly because it was suspected that these PWs engaged in parallel exports). PWs that were rejected were always keen on getting the TCA involved, but the TCA consistently refused to find an infringement in such cases. In such complaints, the TCA merely applied the existing law and characterized the conduct of pharma companies as refusal to deal and held that the relevant drugs might not be deemed as "indispensable inputs" in terms of competition law as products that would merely be resold without any added value do not constitute inputs at all3.

Thus, a dominant pharma company's refusal to deal with an individual PW was characterized as refusal to deal and did not constitute abuse of dominance. Whereas a dominant pharma company's refusal to deal with a whole bunch of PWs was just "something else" (either a "unilateral" anti-competitive agreement or some kind of exclusionary conduct that does not exclude rivals) which was somehow against the law.

Recent Times

In 2016 Roche decided to try again and applied to the TCA to obtain an individual exemption for the quantitative selective distribution network that it planned to establish. Roche was planning to work with 5 to 10 PWs that comply with certain relatively subjective criteria. Since this was a selective distribution network, Roche was planning to prohibit these PWs from selling the contract goods to any other PW which are not included in the network. However, while the examination process was ongoing, Roche made a revision in its agreements and removed this restriction (i.e., PWs that work with Roche would be allowed to sell the contract goods to any other PW). This was a critical move that could have immediately concluded the process since that was the only vertical restriction in the relevant agreement. Yet, following the blueprint of Pfizer, the TCA held that a mere reduction in the number of PWs that Roche would directly work with was sufficient to decide that Roche's agreements would be deemed anti-competitive and not be individually exempted4. Once again, a unilateral conduct was treated as an anti-competitive agreement.

The latest addition to the TCA's collection of "decisions specific to the pharma sector" was the Johnson and Johnson ("J&J") Decision5 in 2020. J&J made an application to the TCA and requested the TCA to confirm that the quantitative selective distribution network (whereby PWs within the network would not be allowed to deal with PWs that are not included) that it is planning to establish for the drugs that have a market share below 40%6 falls within the scope of the block exemption. J&J also mentioned that the drugs that would be included in this network were those that carry the highest parallel export risk, emphasizing that mere contractual export prohibitions were not sufficient to prevent parallel exports and that there may be a shortage of these drugs if the number of PWs that can resell these drugs are not restricted. Despite the explicit provision (para. 172) in the Vertical Agreements Guidelines, which stated that "The Communiqué grants exemption to selective distribution networks, regardless of the nature of the product", the TCA noted that the nature of the product does not justify the establishment of a selective distribution network. Thus, the TCA decided that the agreements do not benefit from block exemption and further held that the conditions for individual exemption are not satisfied. This decision showed, once again, that the TCA applied the law differently when the pharma sector was in question.

The Final Curtain...

Amidst all the accumulated case law of the TCA, Allergan unilaterally decreased the number of PWs that it works with without asking for the TCA's approval (a similar strategy with Sanofi Aventis). Allergan did not prohibit the PWs that it would work with from selling the contract goods to other PWs and thereby ensured that its decision to reduce the number of its direct business partners was a unilateral one.

One of the PWs that it refused to work with immediately made a complaint to the TCA, and a preliminary examination was initiated. Surprisingly, the TCA had a change of heart this time. The TCA held that in the absence of a restriction that prevents contracting PWs from engaging in trade with other PWs, Allergan's action is a unilateral one and that the agreement falls outside the scope of Article 4 (which prohibits anti-competitive agreements) of the Competition Act7.

Furthermore, the TCA stated that Allergan's unilateral conduct should be characterized as refusal to deal and held that there was no abuse since, inter alia, Allergan's drugs do not constitute "indispensable inputs" for PWs.

Hence, Allergan became the first pharma company in Turkey whose decision to work with a restricted number of PWs is deemed to be in compliance with the law.

The Past is History but is Future a Mystery?

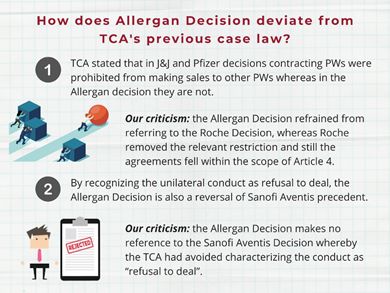

While the Allergan Decision (published on 09.11.2021) is a clear deviation from the previous case law of the TCA, this is not admitted in the relevant decision. Rather than accepting that it is now reversing its former precedents and explaining the reasons why this reversal was deemed necessary in a transparent manner, the TCA chose to claim that the conditions in Allergan's case were different from the former precedents.

In that respect, the TCA referred to J&J and Pfizer

decisions and stated that the main difference between those and

Allergan's case is that in the former contracting, PWs were

prohibited from making sales to other PWs, whereas in the latter,

they are not.

While this statement is true for the J&J case, there are

absolutely zero references to such a prohibition in the Pfizer

Decision. On the contrary, the TCA had unequivocally stated that it

was the reduction in the number of PWs that Pfizer would work with

which prevented the agreements from being individually exempted.

More importantly, the Allergan Decision refrained from referring to

the Roche Decision, whereby Roche explicitly removed the relevant

restriction from the agreements, and still, the TCA held that the

agreements fell within the scope of Article 4 and that they may not

be individually exempted. Thus, there is no doubt that the Allergan

Decision is a reversal of the TCA's precedents with respect to

anti-competitive agreements in the pharma sector.

they are not.

While this statement is true for the J&J case, there are

absolutely zero references to such a prohibition in the Pfizer

Decision. On the contrary, the TCA had unequivocally stated that it

was the reduction in the number of PWs that Pfizer would work with

which prevented the agreements from being individually exempted.

More importantly, the Allergan Decision refrained from referring to

the Roche Decision, whereby Roche explicitly removed the relevant

restriction from the agreements, and still, the TCA held that the

agreements fell within the scope of Article 4 and that they may not

be individually exempted. Thus, there is no doubt that the Allergan

Decision is a reversal of the TCA's precedents with respect to

anti-competitive agreements in the pharma sector.

The decision is also a reversal of the TCA's Sanofi Aventis precedent as far as the legal characterization of the pharma companies' unilateral decision to stop supplying drugs to a large group of PWs is considered. Still, the Allergan Decision makes no reference to the Sanofi Aventis Decision and rather refers to TCA's established case law that dealt with pharma companies' refusal to provide goods to a single PW, whereby the relevant conduct was characterized as refusal to deal.

While the Allergan Decision is an important step forward that seems to put an end to the "special treatment" of the pharma industry, its lack of transparency may negatively affect legal certainty. In the absence of an explicit recognition by the TCA that the Allergan Decision is a "new beginning" in the pharma sector and a confirmation that its future policy will be in line with the Allergan Decision (and not the former precedents), no company can feel absolutely safe.

Due to the lack of transparency on the part of the TCA, we can only speculate as to why there was a change in the TCA's policy. This brings us back to the beginning of this post: The increasing threat of parallel exports and the imminent risk of drug shortages that are facing Turkish citizens. It is highly probable that the TCA realized that not allowing the pharma companies to only work with the most trustworthy PWs could have devastating side-effects and reconsidered its former case law accordingly. Yet, this is not clarified in the Allergan Decision, and it is still questionable whether the said decision provides the pharma companies with a safe harbor.

At least in the Pfizer Decision, which started all this, the TCA frankly emphasized its concern that a reduction in the number of PWs could be accompanied by a reduction in the number of pharmacies and that this would make it harder for certain citizens in remote parts of Turkey to get access to drugs. It is questionable whether this was a valid competition law concern but seeing it transparently made it easier to comprehend the reasoning of the TCA's policy and to predict how it would react in similar situations. Currently, there is much less clarity as the TCA does not even admit that the Allergan Decision is a change of policy, let alone expressly setting forth why the policy was changed.

Given how alarming the current threat of parallel exports in the pharma sector is, it is probable that certain pharma companies would take the leap of faith and plan their strategies by relying on the Allergan Decision as a roadmap. However, if the TCA desires to support pharma companies' struggle against opportunistic parallel traders, it would be beneficial to remove all legal uncertainties as to what is allowed and what is not in the pharma sector.

Footnotes

1. TCA's decision dated 26.09.2018 and numbered 18-34/577-283.

2. https://www.haberturk.com/turk-eczacilar-birligi-nin-verilerine-gore-su-anda-tam-645-ilaca-ulasilamiyor-3246786 (Last date of access: 15.12.2021)

3. While there are a number of similar decisions that concern the pharma industry (TCA's decisions; dated 26.11.2014 and numbered 14-46/845-385, dated 19.07.2017 and numbered 17-23/372-163, dated 29.03.2018 and numbered 18-09/160-80), the most recent decision is the Novartis Decision (TCA's decision dated 11.04.2019 and numbered 19-15/215-95).

4. TCA's decision dated 12.12.2019 and numbered 19-44/732-312.

5. TCA's decision dated 03.09.2020 and numbered 20-40/553-249.

6. 40% used to be the relevant market share threshold in the Block Exemption Communiqué on Vertical Agreements Communiqué and the market share of the seller had to be below that threshold in order for a vertical agreement to benefit from block exemption under the Communiqué.

7. TCA's decision dated 25.02.2021 and numbered 21-10/129-54.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.