1 Legal framework

1.1 Are there statutory sources of labour and employment law?

Several statutes govern employment law in South Africa, the most relevant of which are as follows:

- The Basic Conditions of Employment Act (75/1997) (BCEA) establishes and provides for the regulation of basic conditions of employment.

- The Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act (130/1993) provides for the payment of compensation for death or disablement caused by occupational injuries or diseases sustained by employees in the course of their employment.

- The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108/1996) is the supreme source of law in South Africa, which sets out the rights of citizens (including those regarding labour relations) and defines the structure of the government.

- The Employment Equity Act (55/1998) provides for employment equity regulation, affirmative action measures and prohibition against unfair discrimination.

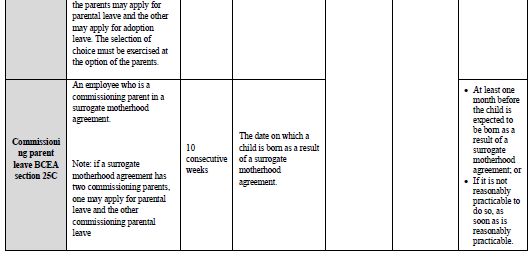

- The Labour Laws Amendment Act (10/2018) amends the BCEA and the Unemployment Insurance Act (63/2001) (UIA) to provide for parental, adoption and commissioning parental leave to employees, and the right to claim parental and commissioning parental benefits from the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF).

- The Labour Relations Act (66/1995):

-

- regulates the organisational rights and registration of trade unions;

- facilitates collective bargaining;

- regulates the right to strike and the recourse to lockout; and

- set outs the procedures for the resolution of labour disputes through the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration, the Labour Court and Labour Appeal Court.

- The National Minimum Wage Act (9/2019) provides for a national minimum wage (NMW) and establishes the NMW Commission.

- The Occupational Health and Safety Act (85/1993) provides for the health and safety of persons at work.

- The Protection of Personal Information Act (4/2013) aims, among other things:

-

- to promote the protection of personal information processed by public and private bodies; and

- to introduce certain conditions so as to establish minimum requirements for the processing of personal information.

- The UIA establishes the UIF to provide payment of unemployment, illness, maternity, parental, commissioning parent or adoption leave benefits to employees.

1.2 Is there a contractual system that operates in parallel, or in addition to, the statutory sources?

Employment contracts are commonly used. While parties may enter into contractual agreements to regulate the employment relationship, the terms and conditions may not be less favourable than those provided for in the BCEA.

In addition, trade unions and employers may enter into collective agreements that regulate terms and conditions of employment.

1.3 Are employment contracts commonly used at all levels? If so, what types of contracts are used and how are they created? Must they be in writing must they include specific information? Are implied clauses allowed?

Yes, employment contracts are used at all levels of employment. Contracts are generally permanent in nature, unless they are fixed for a particular period for a lawful reason. The BCEA requires employers, at the commencement of employment, to provide written particulars of employment in relation to the following:

- the full name and address of the employer;

- the name and occupation of the employee, or a brief description of the work for which the employee is employed;

- the place of work, and, where the employee is required or permitted to work at various places, an indication of this;

- the date on which the employment began;

- the employee's ordinary hours of work and days of work;

- the employee's wage or the rate and method of calculating wages;

- the rate of pay for overtime work;

- any other cash payments to which the employee is entitled;

- any payment in kind to which the employee is entitled and the value of the payment in kind;

- how frequently remuneration will be paid;

- any deductions to be made from the employee's remuneration;

- the leave to which the employee is entitled;

- the period of notice required to terminate employment or, if employment is for a specified period, the date on which employment is to terminate;

- a description of any council or sectoral determination which covers the employer's business;

- any period of employment with a previous employer that counts towards the employee's period of employment; and

- a list of any other documents that form part of the contract of employment, indicating a place that is reasonably accessible to the employee where a copy of each may be obtained.

Even if no written of contract of employment exists, the parties will nonetheless still be considered to be in an employment relationship that will be governed by the provisions of the BCEA in the absence of a formal contractual arrangements. Oral contracts of employment are similarly recognised and a contract of employment need not be in writing to be recognised by law. Implied clauses are permitted. Terms can be implied in an employment contract to reflect the unexpressed intention of the parties or by way of law.

2 Employment rights and representations

2.1 What, if any, are the rights to parental leave, at either a national or local level?

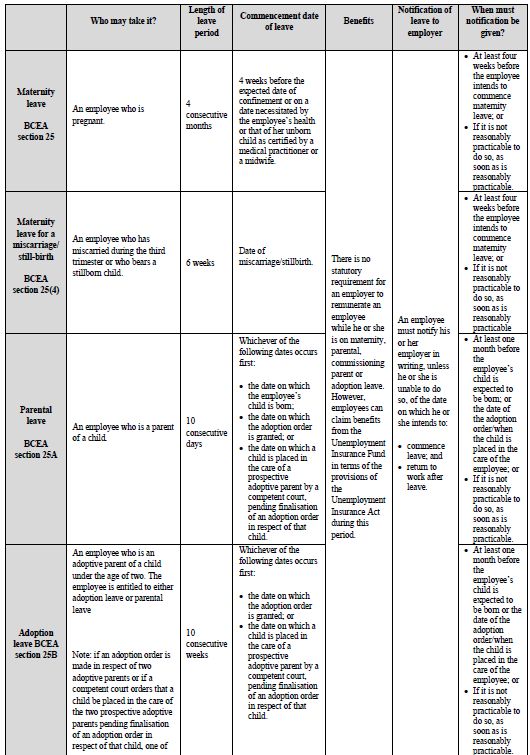

South Africa statutorily recognises maternity leave, parental leave, commissioning parent leave and adoption leave in the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (BCEA).

2.2 How long does it last and what benefits are given during this time?

2.3 Are trade unions recognised and what rights do they have?

Trade unions are recognised in South Africa and play a significant role in industrial relations. Section 23 of the Constitution protects the rights of employees to form and join a trade union, and to participate in the lawful activities and programmes of such a trade union. The Constitution also places particular importance on the protection of freedom of association. The Labour Relations Act (LRA) further emphasises, protects and gives concrete content to these fundamental rights.

Trade unions have certain rights in terms of Section 8 of the LRA. These rights include, among other things, the right to determine their own constitutions and rules and to hold elections for office bearers, officials and representatives. Trade unions also have the right:

- to plan and organise their own administration and lawful activities; and

- to participate in forming federations or to join a federation of trade unions or federations of employers' organisations.

The following organisational rights are afforded to representative trade unions:

- access to the workplace;

- deduction of trade union subscriptions or levies;

- the appointment of trade union representatives;

- leave for office bearers to attend union activities; and

- disclosure of information.

Only representative trade unions can exercise organisational rights, meaning a registered trade union, or two or more registered trade unions acting jointly, that are sufficiently representative of the employees employed by an employer in a workplace.

There is also a statutory process prescribed in the LRA in terms of which trade unions can acquire organisational rights.

2.4 How are data protection rules applied in the workforce and how does this affect employees' privacy rights?

The Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI) sets out the lawful conditions to process another person's information. POPI regulates processes relating to the data subject, the responsible party and the operator. Information can be processed lawfully only if it complies with the extensive conditions set out in POPI, which relate to:

- accountability;

- processing information;

- purpose specification;

- further process limitation;

- information quality;

- openness;

- security safeguards; and

- data subject participation.

POPI applies to all personal and special information of an employee that employers might process. Personal information includes, but is not limited to, the following:

- information relating to the race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, national, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, physical or mental health, wellbeing, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language or birth of the data subject;

- information relating to the education or the medical, financial, criminal or employment history of the data subject;

- any identifying number, symbol, email address, physical address, telephone number, location information, online identifier or other particular assignment to the data subject;

- the biometric information of the data subject;

- the personal opinions, views or preferences of the data subject;

- correspondence sent by the data subject that is implicitly or explicitly of a private or confidential nature, or further correspondence that would reveal the contents of the original correspondence;

- the views or opinions of another individual about the data subject; and

- the name of the data subject, if it appears with other personal information relating to him or her or if the disclosure of the name itself would reveal information about him or her.

Special personal information includes:

- the religious or philosophical beliefs, race or ethnic origin, trade union membership, political persuasion, health or sex life or biometric information of the data subject; or

- the criminal behaviour of the data subject, to the extent that such information relates to

-

- the alleged commission of any offence by the data subject; or

- any proceedings in respect of any offence allegedly committed by the data subject.

In order to comply with POPI, employers should, among other things:

- implement a data protection policy;

- appoint information offices; and

- obtain consent from employees to process their information.

If an employer fails to comply with POPI as the responsible party, it may be subject to imprisonment for between one and 10 years or a fine of between ZAR 1 million and ZAR 10 million. In addition, the employer may be required to pay compensation to the data subject for damaged suffered.

POPI largely came into force on 1 July 2020 and responsible parties were granted a grace period of 12 months, commencing on 1 July 2020, to achieve compliance with its obligations relating to the processing of personal information and special personal information.

2.5 Are contingent worker arrangements specifically regulated?

The South African equivalents of contingent worker arrangements are:

- fixed-term contracts of employment;

- temporary employment services (TES) (labour brokers); and

- independent contractor relationships.

Fixed-term contracts: Fixed-term contracts are permitted in South African labour law. However, to avoid the continuous 'rollover' of fixed-term contracts, amendments to the LRA were enacted – namely Sections 198B(8)(a) and 198B(5) of the LRA, which provide that an employee who is employed on a fixed-term contract for more than three months (whether on a single fixed-term contract or successive fixed-term contracts) is deemed to be a permanent employee for the purposes of the LRA and may not be treated any less favourably than a permanent employee who performs the same or similar work. Section 198B of the LRA applies only to employees who earn below the BCEA earnings threshold of ZAR 211,596.30. These deeming provisions do not apply if:

- the nature of the work for which the employee is employed is of a limited or definite duration; or

- the employer can demonstrate any other justifiable reason for fixing the term of the contract.

In general terms, an individual will be considered an employee for the duration of the contract, which will automatically terminate on the expiration of the fixed term. Automatic termination will not constitute a dismissal, unless the employee reasonably expected to renew a fixed-term contract on the same or similar terms, but the employer offered to renew it on less favourable terms or did not renew it or where an employee had a reasonable expectation of indefinite employment.

TES: This refers to relationships governed by Sections 198 and 198A of the LRA, whereby an employee of the TES renders services to a client of the TES generally for a fixed period of up to three months, where the employee is a substitute for a temporarily absent employee of another employer (the client) or as agreed in terms of a collective agreement. The LRA seeks to protect employees of a TES and particularly those who earn below the BCEA earnings threshold. Accordingly, the TES and the client are jointly and severally liable if the TES contravenes:

- a collective agreement concluded in a bargaining council that regulates terms and conditions of employment;

- a binding arbitration award that regulates terms and conditions of employment;

- the BCEA; or

- a sectoral determination made in terms of the BCEA.

Employees who earn below the BCEA threshold will be deemed employees of the client if they do not perform a temporary service.

Independent contractor relationships: These relationships are purely commercial and involve the rendering of a service to another in the absence of an employment relationship. They are governed by standard contractual principles and not employment law. However, disputes may arise where an individual retained as an independent contractor alleges that he or she:

- is in fact an employee and entitled to certain employment benefits; or

- has been unfairly dismissed at the termination of the contract.

The South African courts will consider the substance of the relationship between the parties, rather than the contractual characterisation of the relationship, in order to determine the true nature of the relationship. In addition, Section 200A of the LRA presumes that a person is an employee if he or she renders services to another and one of seven factors is met. This presumption is rebuttable.

3 Employment benefits

3.1 Is there a national minimum wage that must be adhered to?

As of January 2021, the prescribed national minimum wage (NMW) is set at ZAR 20.76 per hour.

On 20 November 2020, the NMW Commission recommended that the NMW be increased by 1.5% above the rate of inflation (determined in the month of the adjustment) as measured by the Consumer Price Index. On this calculation, as of September 2020, the NMW of ZAR 20.76 per hour could potentially be increased by 4.5%. In addition, the commission recommended that the minimum wage for domestic workers be gradually increased to equal the NMW by 2022. In conjunction with the recommendations, the commission invited the public to make written representations within 30 days (by 20 December 2020). As yet, there has been no announcement confirming the recommended increase for 2021.

In terms of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (BCEA), if an employer fails to comply with the NMW, an employee is permitted to refer a dispute to the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration concerning the failure to pay any amount owing to that employee. In addition, in terms of Section 76A of the BCEA, if an employer pays less than the NMW, it will be subject to a fine that is the greater of:

- twice the value of the underpayment; or

- twice the employee's monthly wage.

For further non-compliance, the fine imposed will be the greater of:

- three times the value of the underpayment; or

- three times the employee's monthly wage.

3.2 Is there an entitlement to payment for overtime?

Yes, there is in respect of employees who earn below the BCEA earnings threshold. 'Overtime' is defined in the BCEA as work during a day or a week in excess of an employee's ordinary hours of work.

Overtime hours can be worked only if:

- the employee has agreed to this (an agreement to work overtime may not require or permit an employee to work more than 12 hours of overtime in any day);

- the overtime is restricted to 10 hours a week; and

- the employee is paid in terms of Section 10 of the BCEA.

An employee must be compensated for such overtime as follows:

- The employer must pay the employee at least one and a half times the employee's ordinary wage for overtime worked; or

- By agreement, an employer may pay an employee not less than an employee's ordinary wage for the overtime worked and grant the employee at least 30 minutes' time off on full pay for every hour of overtime worked, or grant an employee at least 90 minutes' paid time off for each hour of overtime worked.

3.3 Is there an entitlement to annual leave? If so, what is the minimum that employees are entitled to receive?

Yes. Section 20(2) of the BCEA provides that all employees are entitled to annual leave (on full remuneration) of at least one of the following:

- 21 consecutive days in respect of each annual leave cycle;

- by agreement, one day of leave for every 17 days for which the employee worked or was entitled to be paid; or

- by agreement, one hour of leave for every 17 hours for which the employee worked or was entitled to be paid.

Unless the employer and employee agree to calculate leave on a daily or hourly basis, the employee's entitlement to leave must be calculated on the basis of the annual leave cycle.

3.4 Is there a requirement to provide sick leave? If so, what is the minimum that employees are entitled to receive?

Employees are entitled, during every sick leave cycle (a three-year period), to an amount of sick leave equal to the number of days that he or she would usually work over six weeks. As a result, the following amounts of leave are available over a three-year period:

- 30 days for employees who usually work a five-day week; or

- 36 days for employees who usually work a six-day week.

While an employee is absent from work on sick leave, the employer must pay him or her the same wage that he or she would ordinarily have received for working on those day, which payment must be made on the employee's usual payday. However, the BCEA does provide that the parties may agree to a reduced payment being made to an employee for sick days, provided that the number of sick days to which the employee is entitled is increased commensurately. Such an agreement is valid only if the pay for sick leave is at least 75% of the employee's usual wage and the employee's sick leave entitlement over the sick leave cycle is not reduced.

If an employee is absent from work for more than two consecutive days, or is absent on more than two occasions during an eight-week period, the employer may require him or her to produce a medical certificate before paying the employee for the sick leave.

3.5 Is there a statutory retirement age? If so, what is it?

There is no statutory retirement age in South Africa. An employee's retirement age is accordingly determined by:

- the rules of a pension or provident fund, if applicable;

- an employer's retirement policy; or

- agreement between the employee and employer.

In practice, the retirement age ranges between 60 and 65 years.

4 Discrimination and harassment

4.1 What actions are classified as unlawfully discriminatory?

The Employment Equity Act (EEA) prohibits unfair discrimination (direct or indirect) in any employment policy or practice, on the basis of:

- race or colour;

- ethnic or social origin;

- culture, language or birth;

- gender;

- sexual orientation;

- pregnancy;

- marital status or family responsibility;

- age;

- disability;

- HIV status;

- religion, conscience, belief or political opinion; or

- any arbitrary ground.

Discrimination is justifiable only in circumstances where:

- affirmative action measures are taken in accordance with the provisions and purpose of the EEA; or

- it is used to distinguish, exclude or prefer an individual on the basis of a job's inherent requirements.

4.2 Are there specified groups or classifications entitled to protection?

All employees may not be unfairly discriminated against. However, the EEA does provide affirmative action protections for designated groups. The EEA defines 'designated groups' as black people, women and people with disabilities who:

- are citizens of South Africa by birth or descent; or

- became citizens of South Africa by naturalisation before 27 April 1994; or after 26 April 1994 where they would have been entitled to acquire citizenship by naturalisation prior to that date, but were precluded from doing so by apartheid policies.

Affirmative action measures implemented by a designated employer must include:

- measures to identify and eliminate employment barriers, including unfair discrimination, which adversely affect people from designated groups;

- measures designed to further diversity in the workplace based on equal dignity and respect of all people;

- reasonable accommodation for people from designated groups in order to ensure that they enjoy equal opportunities and are equitably represented in the workforce of a designated employer; and

- measures such as preferential treatment and numerical goals (but not quotas) to ensure the equitable representation of suitably qualified people from designated groups in all occupational levels in the workforce and the retention and development of people from designated groups, and the implementation of appropriate training measures.

4.3 What protections are employed against discrimination in the workforce?

Section 51 of the EEA states that no person may discriminate against an employee who exercises any right conferred by the EEA. In addition, no person may threaten to do or do any of the following:

- prevent an employee from exercising any right conferred by the EEA or from participating in any proceedings in terms of the EEA; or

- prejudice an employee because of past, present or anticipated:

-

- disclosure of information that the employee is lawfully entitled or required to give to another person;

- exercise of any right conferred by the EEA; or

- participation in any proceedings in terms of the EEA.

Lastly, it states that no person may favour or promise to favour an employee in exchange for him or her not exercising any right conferred by the EEA or not participating in any proceedings in terms of the EEA.

In addition, Section 60 requires an employer to consult with all relevant parties and take the necessary steps to eliminate alleged conduct in contravention of the EEA. If the employer fails to take the necessary steps, it will be deemed to have contravened the EEA and will be liable.

4.4 How is a discrimination claim processed?

In terms of Section 10 of the EEA, any employee who feels that he or she has been unfairly discriminated against may refer the dispute in writing to the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) within six months of the act or omission that constitutes unfair discrimination taking place. If the CCMA cannot resolve the dispute through conciliation, the matter can be referred by any party to the Labour Court for adjudication. Alternatively, the employee may refer the dispute to the CCMA for arbitration if the employee alleges unfair discrimination on the grounds of sexual harassment or if he or she earns less than the Basic Conditions of Employment Act earnings threshold. In addition, any party may refer the dispute to the CCMA for arbitration if all parties consent to arbitration at the CCMA as opposed to adjudication by the Labour Court.

4.5 What remedies are available?

If the Labour Court decides that an employee has been unfairly discriminated against, it may make any appropriate order that is just and equitable in the circumstances, including:

- payment of compensation by the employer to the employee;

- payment of damages by the employer to the employee;

- an order directing the employer to take steps to prevent the same unfair discrimination or a similar practice from occurring in the future in respect of other employees; and

- publication of the court order.

4.6 What protections and remedies are available against harassment, bullying and retaliation/victimisation?

Harassment, bullying and retaliation/victimisation on the listed grounds will constitute unfair discrimination. The 2005 Amended Code on the Handling of Sexual Harassment Cases in the Workplace provides guidance to employers in dealing with sexual harassment. In addition, given the prevalence of all types of harassment in the workplace, the South African legislature has recently responded to this specific problem in the workplace: on 20 August 2020, the draft Code of Good Practice on the Prevention and Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the World of Work was published for public comment. The draft code provides several key principles to guide employers in the implementation of various strategies to prevent and eliminate violence and harassment in the world of work, and imposes clear duties on employers to ensure a safe working environment. The draft code is still only available for public comment and thus has not yet been enacted into South African law. However, it does provide a useful guideline for the protections soon to be available to employees.

5 Dismissals and terminations

5.1 Must a valid reason be given to lawfully terminate an employment contract?

Yes, a valid reason must be given in order to lawfully terminate an employment contract. An employee may be fairly dismissed only if:

- there are fair and valid grounds for such dismissal (substantive fairness) and;

- such dismissal is effected in terms of a fair procedure (procedural fairness).

The Labour Relations Act (LRA) defines 'dismissal' as the following:

- an employer's termination of a contract of employment with or without notice;

- an employer's failure to renew a fixed-term contract on the same or similar terms or at all, in circumstances where an employee reasonably expected the employer to renew such contract;

- an employer's refusal to allow an employee to resume work after she took maternity leave in terms of any law, collective agreement or contract of employment; or after she was absent from work for up to four weeks before the expected date and up to 12 weeks after the actual date of the birth of her child;

- where a number of employees have been dismissed for the same or similar reasons, an employer's offer to re-employ one or more of them, but refusal to re-employ another or others;

- an employee's termination of a contract of employment with or without notice because the employer made continued employment intolerable for the employee; or

- an employee's termination of his or her employment, with or without notice, after his or her contract of employment has been transferred in terms of Section 197 or 197A of the LRA, where the employer has provided the employee with conditions or circumstances at work that are substantially less favourable than those which were provided by the old employer prior to transfer.

The following grounds will constitute fair reason for a dismissal:

- misconduct;

- incapacity and/or poor performance; and

- operational requirements of the employer (retrenchment).

However, even if an employer has a fair reason to dismiss an employee, if it fails to ensure procedural fairness in the dismissal of the employee, the dismissal will be found to be procedurally unfair. Procedural requirements include conducting a pre-dismissal hearing, among other things. While this need not be a formal enquiry, the employer should notify the employee of the allegations using a form and language that the employee can reasonably understand. The employee should be entitled to reasonable time to prepare his or her response, and should be allowed the opportunity to state a case in response to the allegations with the assistance of a trade union representative or fellow employee. After the hearing, the employer should communicate the decision taken and preferably furnish the employee with written notification of that decision.

5.2 Is a minimum notice period required?

Under the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (BCEA), either party may terminate an employment contract of employment by giving the other party written notice of not less than:

- one week where the employee has worked for the employer for six months or less;

- two weeks where the employee has worked for the employer for more than six months but less than a year; and

- four weeks where the employee has worked for the employer for more than a year, or is a farm worker or domestic worker who has been employed for more than six months.

An employer cannot merely terminate an employee's employment by furnishing him or her with notice. To this end, the employer must adhere to the pre-dismissal requirements. An employer may summarily terminate the employment relationship if the employee is found guilty of serious misconduct, among other things.

5.3 What rights do employees have when arguing unfair dismissal?

There is a statutory right to refer an unfair dismissal dispute to a bargaining council if the dispute falls within the registered scope of that council or with the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) within 30 days of the date of dismissal or, if it is a later date, within 30 days of the employer making a final decision to dismiss or uphold the dismissal. The bargaining council or CCMA will then appoint a commissioner to preside over the unfair dismissal dispute in an arbitration, where oral and documentary evidence will be led by the employer and employee. If the arbitrator finds that the employee's dismissal was unfair, he or she may:

- order the employer to reinstate the employee from any date not earlier than the date of dismissal;

- order the employer to re-employ the employee, either in the role in which he or she was employed before the dismissal or in another reasonably suitable role, on any terms and from any date not earlier than the date of dismissal; or

- order the employer to pay compensation to the employee, which may not be more than the equivalent of 12 months' remuneration calculated at the employee's rate of remuneration on the date of dismissal.

5.4 What rights, if any, are there to statutory severance pay?

If an employee has been dismissed for operational requirements (retrenched), the employee is entitled to severance pay equal to at least one week's remuneration for each completed year of continuous service with the employer in terms of Section 41 of the BCEA. However, if the employee unreasonably refuses to accept the employer's offer of alternative employment with the employer or any other employer, he or she is not entitled to severance pay. In addition to severance pay, on the date of termination of employment, the employee is entitled to:

- his or her salary to date;

- any outstanding leave pay;

- payment in lieu of notice if he or she has not worked the period of notice; and

- any payment due under the employer's pension or provident fund.

6 Employment tribunals

6.1 How are employment-related complaints dealt with?

How complaints are dealt with depends on the nature of the complaint. Most employment complaints are first dealt with internally through dispute resolution mechanisms of the employer, such as grievance hearings. Thereafter, an employee may approach the external statutorily mandated or private dispute resolution bodies.

Statutory dispute resolution forums established under the Labour Relations Act include:

- the dispute resolution arms of bargaining councils in certain industries, including the metal and engineering, motor, public service and chemical industries;

- the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) for those industries that do not have their own bargaining councils;

- the Labour Court; and

- the Labour Appeal Court.

These bodies adjudicate:

- unfair dismissal, unfair labour practice and discrimination disputes;

- disputes relating to organisational rights, strikes and lock-outs; and

- disputes over the interpretation and application of collective agreements.

If the parties so agree or the contract of employment provides therefor, the dispute may be dealt with via private dispute resolution proceedings. However, statutory dispute resolution bodies remain the most prominent route in South Africa.

6.2 What are the procedures and timeframes for employment-related tribunals actions?

Generally, labour disputes are dealt with through bargaining councils or the CCMA.

Referral of the dispute: A party to a dispute will first refer the dispute to the CCMA. The period for referral will depend on the nature of the dispute. Unfair dismissal disputes must be referred within 30 days of the date of dismissal. Unfair labour practice disputes must be referred within 90 days of the alleged conduct taking place. Once the matter has been referred, the bargaining council or the CCMA will appoint a commissioner to preside over the matter, commencing with a conciliation hearing. An applicant can seek condonation for non-compliance with the statutory periods.

Conciliation hearing: Conciliation is an informal process through which the commissioner attempts to resolve the dispute. No evidence is led before the commissioner and he or she cannot make a determination as to the merits of the matter. Instead, commissioners are afforded only the following powers at the conciliation stage:

- to make decisions about the procedure which must be followed during the conciliation proceedings;

- to determine any preliminary points (including the possibility of the joinder of two referrals);

- to direct the way in which the conciliation will proceed, including how he or she wishes to hear each party's side of the story and whether he or she wants to have individual and/or separate meetings with the parties; and

- to make any recommendations regarding settlement.

If the parties are unable to settle at this stage, the commissioner will issue a certificate of outcome certifying that the dispute remains unresolved.

Arbitration: After conciliation, the referring party must then refer the matter to be arbitrated within 90 days of issue of the certificate of outcome. At the arbitration proceedings, the oral and documentary evidence may be led with the party carrying the onus present evidence first, the opposing party then cross-examining the relevant witnesses and re-examination. The same process is followed for the opposing party's witnesses. At the conclusion of the dispute, the commissioner will issue an arbitration award, setting out a summary of the evidence presented, an analysis of the evidence and an award.

Labour Court: Within six weeks of receiving an arbitration award, the parties may approach the Labour Court by way of a motion application to review and set aside the award. In addition, the Labour Court has jurisdiction to preside over action proceedings (or trials).

7 Trends and predictions

7.1 How would you describe the current employment landscape and prevailing trends in your jurisdiction? Are any new developments anticipated in the next 12 months, including any proposed legislative reforms?

The COVID-19 pandemic is very much the central determinant of South Africa's labour landscape for the next 12 months. Employers face increased challenges arising from strict health and safety protocols and regulations which prevent continued operations in industries such as alcohol production, tourism and hospitality. While the Temporary Employment Relief Scheme was implemented in March 2020 to aid employers in providing wage benefits to employees as a result of the effects of the pandemic, the scheme is not permanent and is not a universal panacea.

The roll-out of vaccines in South Africa raises the question as to whether employers can make it mandatory for employees to get vaccinated before returning to work and in doing so, implement a mandatory vaccination policy in the workplace. At present, there is no law governing the vaccine roll-out. Accordingly, if employers adopt a mandatory vaccination policy, this is likely to fall foul of the constitutional right of employees (and all individuals) to security in and control over their bodies. Employers will need to seek to strike the right balance between their health and safety obligations and employees' constitutional right to bodily integrity.

The world of work is likely to continue to adapt to remote working while the COVID-19 pandemic persists; but where industries cannot work remotely, there will likely be increased demands for employers to restructure and dismiss employees based on operational requirements. Many businesses have closed as a result of the financial implications arising from the pandemic and the national lockdown that was implemented on 26 March 2020. As a result, many of the working population now find themselves unemployed. Big business and government need to work together to put in place initiatives to encourage small and medium-sized businesses and entrepreneurship.

Prior to the pandemic, South Africa had begun confronting the reality of several years of state capture. In 2018, the State Capture Commission was established and towards the end of 2020 the National Prosecuting Authority arrested several individuals relating to allegations of state capture. As a form of systemic political corruption in which private interests significantly influence a state's decision making, state capture had reared its head in many workplaces across South Africa, particularly in state-owned entities. As new evidence continues to be presented to the commission and arrests intensify, employers will have to consider implementing forensic investigations, disciplinary proceedings and criminal complaints against employees; and/or making the necessary statutory reports to the requisite authorities where they suspect an employee's involvement in possibly corrupt activities. The same challenges face employers in light of recent corporate crashes pertaining to accounting irregularities.

Gender-based violence (GBV) has come to be coined the 'shadow pandemic' of South Africa. In August 2019, the rape and murder of a university student led to nationwide protests. These protests spotlighted employers' obligations in the fight against GBV and saw the inclusion of GBV as a defined form of workplace harassment in the draft Code of Good Practice on the Prevention and Elimination of Violence and Harassment in the World of Work. The draft code further recognises that anyone can be a victim of GBV, including those who do not conform to gender norms or traditional societal expectations based on gender, such as LGBTQIA+ persons.

8 Tips and traps

8.1 What are your top tips for navigating the employment regime and what potential sticking points would you highlight?

Employment law in South Africa is a highly regulated space which seeks to balance the inherently unequal bargaining power in employment relationships (which primarily stems from South Africa's past apartheid regime) and the business operations of an employer. This forms an important backdrop against which the South African employment landscape should be viewed. Industrial action by trade unions and their members is part and parcel of this landscape. While there is no duty to engage in collective bargaining, many manufacturing, mining, motor and other industries are highly unionised, and collective bargaining plays an important role within this context in reaching wage and other collective agreements.

An employee cannot simply be dismissed in South Africa. It is therefore important for employers to familiarise themselves with the applicable legislation and to appreciate that there are both substantive and procedural requirements that must be complied with, particularly when dealing with unfair dismissal and unfair labour practice disputes. Employment equity measures, including affirmative action which applies to previously disadvantaged individuals, are unique to South Africa and seek to address the unjust discriminatory practices of apartheid. Employment equity obligations are regulated by statute in a number of ways and impose several duties on employers. Many multinationals find it hard to understand and navigate these types of obligations, but must nevertheless be aware of them and comply therewith.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.