The Faceless Assessment ('FA') scheme under India's Income-tax Act, 1961 ('Act') aims to enhance transparency and efficiency by minimizing direct contact between taxpayers and assessment officers. Despite its innovative approach, the scheme encounters challenges relating to natural justice, technical hurdles, and procedural inefficiencies. Concerns include the principles of fair hearing and bias, highlighted by insufficient response times to notices and an arbitrary allotment of cases. Additionally, technical issues and the lack of personal hearings contribute to difficulties in accurate and fair assessments. Addressing these issues could significantly improve the effectiveness and fairness of the FA scheme, aligning it better with its intended goals.

Background

Over time, technology and development become synonymous. The use of technology by individuals and governments has simplified daily activities and enhanced administrative efficiency. However, it also introduced significant drawbacks, such as over-reliance and gaps in knowledge. A prime example of government implementation can be seen in India, where the Ministry of Finance ('MoF') facilitated technological advancements in the Income Tax Department ('Department').

In 2006, the Department launched e-filing of tax returns, followed in 2007 by mandatory e-filing for corporate taxpayers and those requiring audited accounts under s. 44AB of the Act. Subsequently, other taxpayers were included at different intervals. By 2009, the Centralised Processing Centre ('CPC') and viewing of Form 26AS were established, with online verification using Aadhaar and Electronic Verification Code starting in 2015. These steps aimed to enhance taxpayer interaction and streamline assessment proceedings and appeals while improving audit quality and consistency.

In 2015, the Central Board of Direct Taxes ('CBDT') initiated a pilot project for paperless tax assessment, allowing email correspondence with taxpayers in selected cities. This optional facility expanded in April 2017 with the introduction of e-proceedings, enabling electronic communication between Assessing Officers ('AOs') and taxpayers through the e-filing portal. Taxpayers could respond to notices and queries directly on the portal, marking the beginning of e-assessment and reducing reliance on hard copies or emails. By August 2018, CBDT mandated e-proceedings for all assessments in financial year ('FY') 2018-19, except under specific circumstances.

In 2018, the Hon'ble Finance Minister ('FM'), in his budget speech, introduced the FA procedure, which was earlier called the e-assessment scheme. The objective of the scheme (highlighted by the FM in his speech and the memorandum to the Finance Bill, 2018) was to promote efficiency, accountability, and transparency and eliminate direct contact with taxpayers and AO. Despite its objectives, the scheme has faced criticism regarding its constitutionality.

Before exploring these criticisms, reviewing the legal framework governing FA under the Act is essential.

Legal provisions governing the FA scheme

S. 144B of the Act, introduced through an amendment by the Finance Act, 2019 ('FA Act 2019'), became effective from 01.04.2021. It outlines the procedure for FA aimed at reducing physical interaction between taxpayers and the tax authorities.

Under s. 144B of the Act, the national e-assessment centre ('NeAC') acts as a central agency facilitating communication between taxpayers and various assessment units ('AUs'). NeAC assigns cases randomly to regional e-assessment centres ('ReACs') to maintain anonymity and impartiality. Several specialized units, like verification units ('VUs'), technical units ('TUs'), and review units ('RUs'), play distinct roles. These include conducting assessments, verifying information, providing technical support, and reviewing assessment drafts.

Notices and communications detailing assessment issues are electronically sent to taxpayers, who must respond through the e-filing portal within specified timelines. Taxpayers submit their responses and relevant documents electronically, with physical submissions only requested in specific cases. Following the assessment by the AU, a separate review unit ensures fairness and accuracy in the draft assessment order. NeAC finalizes the assessment order, which is then communicated to the taxpayer, who retains the right to seek rectification or file an appeal.

S. 144B of the Act also encompasses provisions for penalties and prosecution in cases of non-compliance or submission of false information.

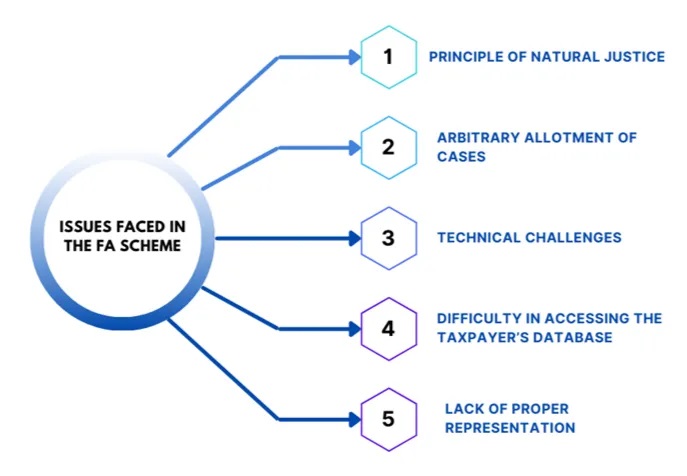

Issues faced after the incorporation of FA

A. The first issue concerns the principles of natural justice

One of the primary concerns raised after the introduction of FA is its alignment with the principles of natural justice. Before delving deeper, it is crucial to understand the concept of 'natural justice' in legal terms.

While the concept of natural justice is not explicitly defined in the Indian Constitution or any statute, it is universally recognized across legal systems. It mandates that individuals receive a fair and impartial hearing before any decision affecting them is made.

The principles of natural justice are based on the following two primary principles:

a. Nemo Judex In Causa Sua, i.e., the rule against bias, is to abstain from unfair activity in a conscious state in relation to the facts of a particular case. The bias could be actual, imputed, apparent, personal, primary, subject matter or departmental.

b. Audi Alteram Partem, i.e., right to a fair hearing, which requires that individuals are not affected by the decisions affecting their rights or legitimate expectations unless they have been given prior notice of the case against them, a fair opportunity to answer them, and an opportunity to present their own case.

The question arises: does FA violate these principles of natural justice?

Since the introduction of FA, it has faced significant criticism, particularly concerning its alignment with the principles of natural justice. Under FA and the provisions of the Act, a show cause notice ('SCN') must be issued whenever there is a proposed variation in the declared income. The controversy revolves around s. 144B(1) of the Act, which sets out time limits for conducting assessments in a faceless manner. Notably, s. 144B(1)(ii) of the Act specifies a time limit for taxpayers to respond to the notice issued under s.143(2) of the Act by the NFAC, whereas other subsections do not provide a clear time frame for replying to the SCN.

This absence of specified time limits can lead to situations where the NFAC provides insufficient time for taxpayers to respond adequately. This practice has been criticized for its potential to undermine natural justice principles, as affected taxpayers may not have adequate opportunity to defend themselves.

The Hon'ble Supreme Court ('SC'), in the case of UMC Technologies Private Limited v. Food Corporation of India and Anr.1 emphasized that the principle of natural justice requires authorities to notify affected parties of the case against them sufficiently in advance, ensuring clarity on the grounds for any proposed action or penalty. Such notice should be adequate, and the grounds necessitating action and/or penalty proposed should be explicitly mentioned and unambiguous. Further, in the case of CIT v. Panna Devi Saraogi2 and Smt Ritu Devi v. CIT3, the SC held that providing only one day for the Assessee to furnish his reply was inadequate and amounted to denial of a fair opportunity.

Furthermore, the Delhi High Court ('DHC'), in cases of KBB Nuts (P.) Ltd. v. National Faceless Assessment Centre (Earlier National e-Assessment Centre, Delhi)4 andRKKR Foundation v. National Faceless Assessment Centre, Delhi5, deliberated on whether providing one or two days for the Assessee to reply to SCNs is sufficient. The DHC concluded that such limited timeframes violate the principles of natural justice.

Due to the information traveling back and forth between various assessment units, there have been instances where the assessee's submissions are overlooked by the Department. The Bombay High Court ('BHC'), in the case ofRaja Builder v. NFAC6, held that any orders passed by the NFAC without considering the assessee's response should be stayed, and the taxpayer must be given a reasonable opportunity to be heard.

Even though there is no provision prescribing a specific time limit, s. 144B(9) of the Act provides relief to the assessee. It states that non-compliance with the procedures laid down under s. 144B of the Act renders the entire assessment proceeding null and void, a defect that cannot be cured.

However, despite the criticism, the Allahabad High Court ('AHC'), in the case of Sapna Flour Mills v. Union of India7, upheld the constitutional validity of FA under s. 144B of the Act. The AHC observed that the enactment of FA aimed to facilitate ease of doing business. It also emphasized the responsibility of the CBDT to address flaws and ensure a balanced and efficient FA process.

In summary, while FA aims to streamline processes, concerns persist regarding its adherence to the principles of natural justice, particularly concerning the adequacy of time granted to taxpayers to respond to notices and defend their positions effectively.

B. The second issue pertains to the arbitrary allotment of cases in the FA scheme

Another issue that has arisen since the enactment of FA is the arbitrary allotment of cases. Currently, the NeAC delegates cases to AUs through an automated system without considering the experience of the specific FAO. This can result in complex cases being assigned to relatively inexperienced officers or vice versa.

Such arbitrary allotment often leads to slower case disposal, as inexperienced FAOs may struggle to fully understand and appreciate the complexities of certain cases, thereby affecting the efficiency and effectiveness of the assessment process.

C. The Third Issue pertains to the technical challenges in the FA Scheme

A third issue with the FA scheme is the technical challenges taxpayers and officials face. One major problem is the uneven distribution of internet services across India. Many citizens lack reliable internet access, making it difficult to comply with online procedures.

Moreover, the information requested through various notices is often bulky and voluminous, posing difficulties when uploading to the income tax portal due to file size limitations. Taxpayers frequently encounter technical glitches that hinder the submission process.

Additionally, FAOs often cannot access case records held by the Jurisdictional Assessing Officer ('JAO'), which hampers their ability to fully understand and assess the cases effectively. This lack of access to complete information further complicates the assessment process, impacting the overall efficiency of the FA scheme.

D. The fourth issue relates to issues with accessing the taxpayer's database in the FA Scheme

An issue with the FA scheme is the challenge of accessing the taxpayer's database. The FA operates without human intervention, relying solely on email communication between taxpayers and the tax department.

However, there are instances where the taxpayer's email ID is not updated, often due to changes in the concerned person or the authorized representative. This can result in non-submission or delays in submitting the required information, as the communications may not reach the correct recipient in a timely manner. This lack of updated contact information complicates the process and hinders efficient information exchange.

E. The fifth issue is with regard to the lack of representation in the FA scheme

This issue is practical in nature as there is no personal interaction between the taxpayer's representative and the NFAC or Regional Faceless Assessment Centre ('RFAC'). Communication is solely through written submissions. This can be problematic if the taxpayer faces an adverse outcome due to their consultant or advocate's 'poor draftsmanship.' There are instances where taxpayers are not granted the opportunity for a personal hearing to make oral submissions before the income tax authorities. This lack of personal interaction can result in unfair assessments. In notable cases like Lemon Tree Hotels Ltd. v. National Faceless Assessment Centre8 andRitnand Balved Education Foundation (Umbrella Organization of Amity Group of Institutions) v. National Faceless Assessment Centre9, the DHC stayed the operation of assessment orders on the grounds that the assessee was not granted a personal hearing.

Suggestions from various tax experts on improving the FA scheme

In the article titled 'First year completion of faceless assessment regime – Hit or a miss, the journey so far,' Mr. Arjun Khandelwal and Rahul Valiramani, Chartered Accountants, suggest that the FA scheme should have been introduced in a phased manner. They recommend a trial and test method between the Department and the assessee to identify potential issues before full implementation. Additionally, they point out that the government failed to provide adequate guidance to field officers on conducting assessments in accordance with the due process of law.

Mr. Ajay Rotti, founder and CEO of Tax Compass, shared his views on FA: 'The government's initiative, aimed at fostering transparency and tackling corruption, introduced a well-meaning scheme. Previously, in IT assessments, there existed a system where officers were identified, allowing face-to-face interactions for clarifications. The shift to faceless assessments curtailed corruption by eliminating direct interactions and officer identification, establishing a comprehensive trail of proceedings.'10

Mr. Shriram Subramaniam, Managing Director of InGovern, emphasized the importance of meticulous record-keeping and professional guidance:

'Taxpayers must proactively ensure meticulous records, allocate ample resources, both in systems and skilled professionals, and seek guidance from qualified tax advisors. Discrepancies between reported turnovers demand a closer inspection and alignment between GST filings and income tax declarations.'11

Mr. Giri, Secretary General of Empower India, highlighted the need for improvements to achieve the vision of the FM: 'The current regime has introduced a host of mechanisms that have helped in the collection of taxes. However, the faceless assessment needs to improve to be able to live up to the vision of the finance minister of the country. The recommendations are a step towards creating a more efficient and taxpayer-friendly assessment process, ultimately contributing to India's competitiveness on the global stage.'12

Conclusion

While well-intentioned and aimed at fostering transparency and reducing corruption, the FA scheme has encountered several challenges and criticisms since its implementation. The scheme has been criticized for potentially violating principles of natural justice. The lack of clear time limits for responding to notices and the insufficiency of time provided in some cases undermine the taxpayer's ability to defend themselves effectively. The automated system for case allotment can lead to inefficiencies, as complex cases may be assigned to less experienced officers, slowing down the assessment process and affecting the quality of assessments. Further, the technical challenges complicate the entire scheme, posing significant hurdles for taxpayers and the authorities, resulting in delays or non-submissions and affecting the assessment process. Lastly, the lack of opportunities for personal hearings can lead to unfair assessments.

In conclusion, the suggestions mentioned above, such as introducing the FA scheme in a phased manner and providing adequate guidance to field officers, could mitigate many of these issues. Further enhancing the FA scheme to be more taxpayer-friendly and efficient will contribute significantly to India's global competitiveness.

Footnotes

1. Civil Appeal No. 3687 of 2020

2. [1970] 78 ITR 728 (Calcutta)

3. [2004] 141 Taxman 559 (Madras)

4. [2021] 127 taxmann.com 194 (Delhi)

5. 2021] 127 taxmann.com 643 (Delhi)

6. [2021] 127 taxmann.com 339 (Bombay)

7. [2022] 145 taxmann.com 557 (Allahabad)

8. [2021] 128 taxmann.com 409 (Delhi)

9. (2021) 437 ITR 114

11. Idem

12. Idem

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

We operate a free-to-view policy, asking only that you register in order to read all of our content. Please login or register to view the rest of this article.