In BEABA v Biba (Zhejiang) Nursing Products Co., Ltd [2022] SGIPOS 5, BEABA successfully opposed Biba (Zhejiang) Nursing Products Co.'s ("Biba") applications for a stylised BEABA mark on various grounds, including bad faith. This update focusses on the bad faith ground of opposition and how an inference of bad faith can potentially be drawn from circumstantial evidence.

Background

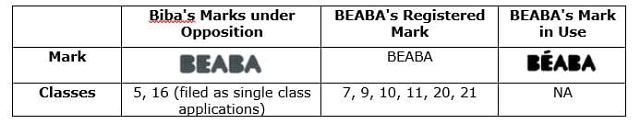

The marks which Biba and BEABA relied on are:

Similarities in marks and goods

Before delving into the allegation of bad faith, the Registrar first determined that the registered marks were visually similar and aurally and conceptually identical.

Biba's class 5 goods (e.g. diapers) and BEABA's class 21 goods (e.g. potties) were also considered similar. However, Biba's class 16 goods were distinguishable from all of BEABA's goods.

Accordingly, BEABA succeeded on the confusion-based grounds of opposition with respect to class 5 but not class 16. The Registrar would refer again to the similarities in the marks and goods when assessing bad faith.

What is bad faith?

The Registrar reiterated that the concept of bad faith is highly fact-specific and "embraces not only actual dishonesty but also dealings which would be considered commercially unacceptable". Further, an allegation of bad faith must be "sufficiently supported by the evidence, which will rarely be possible by a process of inference".

In support of their claim, BEABA submitted that Biba could not have been unaware of BEABA's marks, given that:

- Both parties were involved in the same business of distributing childcare products;

- BEABA's goods have been sold in Singapore since 2010 and in China (where Biba is based) since 2013;

- BEABA's marks were registered in Singapore since 2014 and in China since 2015; and

- BEABA has used their marks widely online.

Biba did not deny knowledge of BEABA but claimed they had coined their mark from the words "Beautiful Baby". Further, Biba argued that the Registrar should not draw adverse inferences against them as BEABA had not applied for cross-examination, thereby depriving Biba of an opportunity to substantiate their evidence.

The Registrar held that Biba had failed to provide a credible explanation about the development of their mark, noting in particular the almost identical stylisation of Biba's mark to the BEABA mark in use. This led the Registrar to draw an "irresistible conclusion" of copying and a dishonest intention to take advantage of BEABA's reputation. Whether BEABA applied for cross-examination was irrelevant since Biba clearly knew that BEABA was relying on the bad faith ground yet chose to file a brief response without supporting evidence.

Finally, the Registrar clarified that the bad faith ground is distinct and independent from the issue of confusing similarity. Hence, BEABA successfully blocked Biba's applications in both classes 5 and 16 on this ground, despite the Registrar's earlier conclusion that Biba's class 16 goods were not confusingly similar to BEABA's.

Takeaways

The Courts of Singapore have emphasised that bad faith is a serious claim and must be sufficiently supported by evidence. However, brand owners should not be too quick to dismiss this ground from their opposition strategies, especially since establishing bad faith will obviate the need to prove a likelihood of confusion. This decision illustrates that it may be possible to prove bad faith even if a brand owner cannot gather direct evidence of copying. Ultimately, it will depend on the facts of each case.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.