Protections against workplace sexual harassment have been substantially improved following changes to the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) (SD Act), the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) and the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) (AHRC Act), which commenced on 11 September 2021. The amendments implement important changes recommended by Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Kate Jenkins, following the Respect@Work: National Inquiry into Sexual Harassment in the Workplace (2020).

Overview of changes

The SD Act has been varied to:

- extend its coverage to interns, volunteers and self-employed workers, as well as to state public servants, members of parliament, their staff, and judges at all levels of government

- introduce a new provision prohibiting unlawful harassment of a person on the grounds of their sex

- simplify process of making complaints to the Australian Human Rights Commission.

The AHRC Act has been varied to give complainants up to 24 months to bring a claim (as opposed to the previous time frame of six months).

The FW Act has also been varied to:

- give the Fair Work Commission power to make an order to stop sexual harassment in the workplace

- grant a universal right to an employee to take leave following a miscarriage.

This article examines key implications for public sector employers seeking to design effective policies addressing sexual harassment and sex-based discrimination.

New prohibition against sex-based harassment

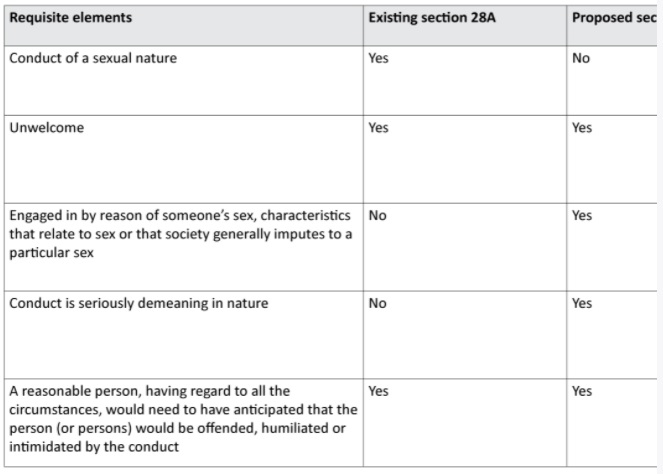

The SD Act currently prohibits sexual harassment (section 28A) and sex-based discrimination (section 5). The new prohibition under section 28AA against harassment on the ground of sex is intended to capture harassing conduct that is seriously demeaning, but not necessarily sexual.

The differences between the existing prohibition against sexual harassment and the new section 28AA provision are explained in the table below:

The Government believes new section 28AA has strengthened the anti-discrimination law framework by clarifying that harassment on the basis of sex is unlawful. A person who experiences sex-based harassment will have a clear, streamlined pathway for addressing that conduct, rather than relying on existing sexual harassment (to the extent the conduct involved can be classified as sexual in nature) or sex discrimination provisions.

Of course, there is the potential that applicants will inevitably make their claim around both provisions, given the element of "conduct of a sexual nature" for the purposes of section 28A is now broadly interpreted and includes anything that might hold up an object of conduct to sexual ridicule. If so, the changes may lead to duplicity rather than simplification of litigation.

Like section 28A, harassing conduct on the ground of sex contravening section 28AA would need to be sufficiently serious or sustained to meet the objective threshold of offensive, humiliating, or intimidating. However, unlike section 28A, new section 28AA would require the conduct to also be "seriously demeaning". This is intended to exclude mild forms of inappropriate conduct based on a person's sex. The explanatory memorandum cites the example of a mechanic providing an overly simplistic and condescending explanation to a female client about the car repairs the mechanic had undertaken on her car, which while irritating for the female client, would not contravene section 28AA.

The requirement for sex-based harassment to be "seriously demeaning" in order to be actionable was criticised by some organisations making submissions to the Senate Education and Employment Legislation Committee's review of the Bill. The Government states that this merely reflects the type of conduct that has been found to constitute sex-based harassment in the case law. However, unresolved questions arise from the concept. To demean is to debase or degrade another person. Is that to be assessed subjectively based on the evidence of the person allegedly demeaned, or objectively based on what a reasonable person observing the interaction would consider? Does the requirement need proof of some intent by the person engaging in the conduct?

Expanded coverage for the SD Act

The provisions in the SD Act that make sexual harassment in the workplace unlawful adopt the concept of a person conducting a business or undertaking (PCBU), which is used in work health and safety legislation in most Australian jurisdictions. This captures sexual harassment and sex-based harassment that occurs between people who do not fall within the definition of employer and employee, but who nevertheless have a workplace relationship. Examples are interns, volunteers and people who are self-employed.

A worker is protected under the new provisions even if the sexual harassment occurs at times or places when work is not actually performed, e.g. attending a pub to continue a discussion begun at the principal workplace.

The amendments mean that a person who causes, instructs, induces, aids or permits another person to engage in sexual harassment is also liable under the SD Act. For example, if a manager encourages one of their junior staff to sexually harass another staff member, the manager may be held liable as an accessory to the harassment. Further, if an employee encourages a fellow employee to harass a person on the basis of their sex, but does not engage in this conduct themselves, they may also be held liable as an accessory under this provision.

The Government declined to include provisions in the SD Act creating a positive duty on PCBUs to provide a harassment-free workplace. The Government argues that existing work health and safety laws already contain a positive duty to prevent exposure to health and safety risks, so far as is reasonably practicable, including the risk of being sexually harassed. State and territory governments have been asked to develop specific regulation and a Code or Practice dealing with sexual harassment. Australian Public Service (APS) agency heads must already uphold and promote the APS Employment Principle of providing a safe and discrimination-free workplace.

Supporting changes to the FW Act

The FW Act anti-bullying jurisdiction has been expanded to allow the Fair Work Commission (FWC) to make an order (on and from 11 November 2021) to stop sexual harassment in the workplace.

Workers who reasonably believe that they have been bullied and/or sexually harassed at work may apply to the FWC for an order to stop the bullying and/or sexual harassment, in the same way as a bullied worker can seek an anti-bullying order. However, unlike bullied workers, the applicant will not need to show the sexual harassment was repeated or part of a pattern, and the application can be made in one-off cases. The applicant will also not need to show a risk to health and safety, given sexual harassment is a known and accepted work health and safety risk. However, the sexual harassment needs to be "at work". Like bullying, this can be when the worker is engaged in some other activity which is authorised or permitted by their employer, and include at work events and coffee breaks.

On 10 July 2021, an amendment to Fair Work Regulations provided that sexual harassment is grounds for serious misconduct, disentitling an employee to minimum statutory notice under the FW Act. For the purposes of the Regulation, sexual harassment is defined as conduct that is prohibited by section 28A of the SD Act. A note has been inserted in the FW Act unfair dismissal provisions to state (what inarguably does not need stating in our view) that sexual harassment is a valid reason for dismissal for the purposes of unfair dismissal claims.

The entitlement to compassionate leave provided in the National Employment Standards of the FW Act has been changed to enable an employee to take up to two days of paid compassionate leave (unpaid for casuals) if the employee, or employee's current spouse or de facto partner, has a miscarriage. Miscarriage is defined as the spontaneous loss of the embryo or foetus before 20 weeks' gestation.

Key points for public sector employers

Employers should review the systems they have in place that are designed to address sexual harassment and sex-based discrimination to determine whether they:

- respond to reports of unwanted or offensive behaviour early

- encourage workers to report sexual harassment

- manage reports and complaints effectively and sensitively

- take action where appropriate against perpetrators

- provide information, instruction, training and supervision to prevent unlawful behaviour.

Leave policies and procedures will need to be updated to deal with the expanded rights to take compassionate leave.

This publication does not deal with every important topic or change in law and is not intended to be relied upon as a substitute for legal or other advice that may be relevant to the reader's specific circumstances. If you have found this publication of interest and would like to know more or wish to obtain legal advice relevant to your circumstances please contact one of the named individuals listed.