GME Pty Ltd v Uniden Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 520

In a recent decision concerning design infringement, the Federal Court of Australia determined that Uniden Australia's mobile radio product embodied a design that was substantially similar in overall impression to GME's registered design for a microphone.

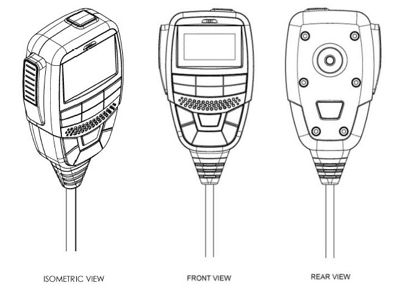

GME, an Australian engineering and manufacturing company that produces radios and emergency beacons, is the owner of a registered design for a microphone (Registered Design), as depicted in the following drawings:

GME alleged that Uniden Australia, which is part of the Uniden Corporation of Japan, a global wireless communications and consumer electronics organisation, threatened to infringe the Registered Design by launching its XTRAK UHF mobile radio product (XTRAK product), as shown below:

Uniden denied infringement. It did not otherwise allege that the Registered Design was invalid.

Infringement of the Registered Design

In assessing whether a product infringes a registered design, the Court must consider whether the product is identical, or substantially similar in overall impression, to the registered design. In making this assessment, the Court must give more weight to similarities between the designs than to differences between them (section 19(1) of the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (Designs Act)) and must have regard to the following factors (section 19(2) of the Designs Act):

- the state of development of the prior art base for the design;

- any statement of newness and distinctiveness filed with the design application (and any particular visual features identified in that statement as new and distinctive);

- where only part of the design of the product is substantially similar to the Registered Design, the amount, quality and importance of the parts of the design, having regard to the context of the design as a whole; and

- the freedom of the creator of the design to innovate.

In determining these matters, the Court must apply the standard of a person "who is familiar with the product to which the design relates, or products similar to the product to which the design relates" – this person is defined as the "informed user" (section 19(4) of the Designs Act).

Informed user

Both parties filed expert evidence to assist the Court in determining the above matters. GME relied on the evidence of Graeme MacDonald, a designer since 1981 and, since 2000, a director of a company which provides industrial design and product engineering services. Mr MacDonald had experience in industrial and mechanical design of handheld radios (including on at least five specific projects) and had experience disassembling competitor products to examine the construction and styling of those products.

Uniden relied on the evidence of Andrew Simpson, an industrial designer since 2004, who had been a principal of a design agency since 2005. Mr Simpson had no direct experience designing handheld radios, but had experience designing products for a broad range of industries (including outdoor furniture, vertical gardens, lighting and electronic vehicle charging stations). He had also been involved in designing consumer electronic products and was a guest lecturer and tutor in industrial design at two Sydney universities. Though Mr Simpson had no specific experience designing handheld microphones, he gave evidence that he was an offshore yachtsman and had for many years used handheld microphones, including some which comprised the prior art, and that he had provided bushfire and police services with design advice relating to use of microphones.

The experts provided a joint report to the Court and gave evidence concurrently during trial.

Justice Burley determined that both experts met the description of an informed user, but that Mr MacDonald clearly had more relevant experience in designing the products in question. Mr Simpson's knowledge was determined by the Judge to come from his general qualifications combined with his personal use of products similar to those relevant to the case.

Consideration of the prior art

As set out in the case of Hunter Pacific International Pty Ltd v Martec Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 796, and cited by Justice Burley, where there are small differences between the registered design and the prior art, there will be no infringement of the registered design if there are equally small differences between the registered design and the allegedly infringing product. Conversely, if the registered design has made a more significant advance over the prior art, it is more likely that common features between the registered design and the allegedly infringing product will support a finding of infringement.

Justice Burley undertook a detailed consideration of the prior art and determined that there were a number of features of the prior art devices common to handheld microphones. However, there was considerable variability within the design characteristics of each of those features.

In terms of relevant functional aspects of microphones and freedom to innovate, Mr MacDonald's evidence was that there were basic ergonomic requirements that had to be considered when designing radio frequency products. For example, the device should be able to be held in the hand (and the PTT (press to talk) button should be in a place to enable it to be pressed by the thumb or index finger) and the user interface should be simple enough to use without reference to a detailed instruction manual. Otherwise, Mr MacDonald opined that there was generally freedom with respect to the design of the remainder of the product.

Mr Simpson's evidence was that there were functional and ergonomic limitations which had the effect of restricting design choices and that, contrary to Mr MacDonald's opinion, some of these elements were not stylistic. In his view, the location and shape of the screen, the location of the buttons and the grommet were all dictated by function and that, whilst the designer had freedom to create different "visual languages" around those functional requirements, there were rules that had to be followed to make the product "pleasing, saleable and easy to use".

Justice Burley accepted that there were basic ergonomic requirements the designer had to consider when designing radio frequency products (and, in particular, handheld and microphone products) that limited the designer's freedom to innovate and that the basic architecture of a microphone will typically include elements such as the PTT button, buttons, a speaker, a microphone and a grommet. However, his Honour did not accept that "functional limitations 'drive the design'" or that all of the designs, as Uniden submitted, looked so similar. His Honour therefore preferred the evidence of Mr MacDonald that there was considerable scope for variability within each of the features.

Infringement of the registered design

Justice Burley considered the similarities and differences between the GME design and the XTRAK product, noting the similarity of the product shapes, PTT button shape and arrangement, the screens and screen surrounds and button shape and array. In terms of differences, his Honour noted in particular the difference between the XTRAK product's smooth silhouette and the Registered Design's step-in silhouette which formed part of the lower third of the product design. Whilst Mr Simpson contended that the step-in feature of the Registered Design was the "dominant visual element", his Honour determined that, whilst it was a design feature, it was not a strong, let alone the dominant, visual element of the design.

After considering the similarities and differences between the XTRAK product and the Registered Design, and, as required by section 19(1) of the Designs Act, placing more weight on the similarities between the designs than the differences, Justice Burley considered that the XTRAK product embodied a design that was substantially similar in overall impression to the Registered Design. His Honour noted that, having regard to the prior art, the informed user would regard the XTRAK product to be more similar in overall impression to the Registered Design than any of the other prior art devices.

Relief

In a subsequent decision on relief, Justice Burley made declarations of infringement, ordered an injunction preventing Uniden from dealing with the XTRAK products whilst the Registered Design remained registered and ordered Uniden to pay GME's costs. His Honour declined to make orders for delivery up and takedown of materials about the XTRAK product, on the basis that an injunction had been ordered against Uniden and there was no reason to believe Uniden would not comply with the injunction. The fact the XTRAK products had never been sold in Australia supported this approach.

Key takeaways

- Registered designs can provide a reasonably streamlined and cost effective way of protecting the visual features of a product. As this case demonstrates, the features of a competitor's product do not need to be identical for it to infringe a registered design; they need only be substantially similar in overall impression to the registered design.

- This dispute was dealt with incredibly quickly – proceedings were issued on 11 March 2002, there was a one-day trial on 19 April 2022 and judgment was handed down on 9 May 2022 – which is likely due, in part, to the parties narrowing the issues in dispute (i.e., Uniden not alleging that GME's design was invalid). Although GME initially made a claim for urgent interlocutory relief when it commenced proceedings, the case was instead fast tracked, with Uniden providing undertakings to the court not to deal with the XTRAK product in the interim.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.